A few posts ago, Liz asked what I thought the Quaker view of the devil is, and I gave a quick response, in the comments area, but I'll try to give a more full answer here. This is a sticky topic, because believing in a personified devil figure is not very popular in our postmodern culture.

It's obviously very difficult to pin down the "Quaker view" on anything, so I'll do my best and then say what I think.

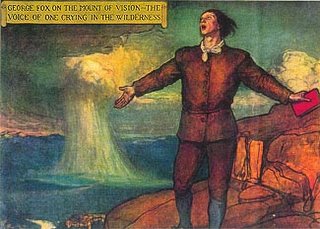

In early Quakerism there was a lot written about being involved in the "Lamb's War," that is, the war of Jesus against the powers of darkness. I don't think they probably questioned whether there was a personified devil any more than they questioned whether there was a personified God. To the early Friends, having faith is to become a soldier in a war against evil (to be distinguished clearly from the War on Terror!). They recognized that there were evil forces at work, and that it took sacrifices in order to advance the Kingdom of God. This Kingdom is not a flesh-and-blood kingdom, it's not going to be a government or even a form of government (although Penn kind of tried that), but it's a coming age when the righteousness and justice of God will rule because all will know and follow God. Their work as Christians and as Friends (which were one and the same to them, as far as I can tell) was to follow their commander, Jesus/Holy Spirit, even when it meant death. And it often did mean death, or at least imprisonment, because they were sincerely fighting against evil, and evil was fighting back.

As far as Quakers today, Quakers in "developing" countries I think generally would believe in a personified devil. They are mainly on the evangelical end of the Friends spectrum and tend to read the Bible more literally. Their cultures generally are more spiritual, in that they believe in a spirit world that effects daily life all the time, for god and evil. So they can understand Christianity with its duality of good and evil spirits.

Although there isn't exactly a personified devil in the Old Testament (the serpent is never named as the devil, the "adversary" in Job is interpreted as the devil but not so named), a concept of a personalized devil has developed by New Testament times: Jesus is tempted by THE devil (given a definite article in Greek, meaning it is a specific entity not just a force of evil or a demon), the Lord's Prayer in Matthew says "Deliver us from the Evil One," (again with the definite article in the Greek), and Jesus and his disciples expel demons from people--and these are just a few examples. So there is definitely biblical reason to believe in personified evil spirits and one head devil.

American Christian Quakers don't talk about the devil much, at least in circles I've been in. There is talk of sin and sinful nature, and I think it's more popular to think of an evil force that corrupted our human nature, as it was supposed to be created, from the Image of God to a distorted image that can't help but sin until it's regenerated by God's grace through Christ, and through the Holy Spirit helping us to recognize God's grace and accept it. Many American Quaker Christians also believe there is a devil who personifies evil and may encourage acts of evil in the world.

Some people think that demon possession is really mental disorders, and Jesus could heal the person's mind as well as their body, so he wasn't expelling demons but healing the mind. But this doesn't really make sense with the biblical witness because the demons can talk, they recognize Jesus as the Son of God, and they can be driven out of a person and into pigs.

And some American Quakers don't believe in a devil at all, especially those who do not identify themselves as Christians or who think the Bible is an interesting and helpful story but shouldn't be taken literally at all. Probably some American Quakers don't believe in evil, only in structural injustice, which causes evil things to happen, which influences more evil things...etc.

So what do I think? Well, philosophically and theologically, from a Christian perspective, there are many problems with believing in a personified devil, and there are many problems with not believing in said devil. If there is a devil, where did it come from? Did God create it? If so, can God create evil? There is no place in the Protestant Bible where the story we're told of Satan as a fallen angel appears, although I think it's in the Apochrypha (which is in the Catholic Bible), so probably was written sometime between the Exile and the time of Jesus (about 500 years). So pretty much in the Protestant Bible, the devil just shows up in Matthew 4 for the first time and there is no indication where it came from. So it's hard to know if Judaism was just influenced by its neighbors, espeically Zorastrians who were complete dualists, and took on the idea of a personalized devil when there really isn't one, or if the understanding of the evil spiritual world kept developing over the years as they learned to understand the good spiritual world more fully as well.

Another problem is dualism. If we believe in the devil, does that mean there's another force that is outside of God? If God can't take any part in evil, how could it come to be without God? Is there another eternal power besides God? Christian doctrine says no: God is the only infinite. So where could this evil being have come from? We can explain sin as a rupture in relationship with God, and that God din't create this but created the possibility. But it's harder to explain an actual entity whose purpose and personhood is evil incarnate.

At the same time, as a Christian I can't just ignore passages in the Bible that talk about a personified devil. I can choose to believe that they are allegorical, but I can't just discard them without thinking about them.

And I've been thinking about this issue a lot lately for a couple reasons. First, I read an autobiography of a Christian woman from South Korea for my church history class, and she said she hadn't believed in demons but then she saw someone with a demon, and she and another minister prayed, they talked to it, and eventually it came out of the man. This autobiography was written in 1988. I don't think she's making this up. We could explain it away by saying the person had a mental breakdown and believed there was a demon speaking through him but he made it all up, but he wasn't even a Christian and knew nothing about Christianity and yet the demon knew the name of Jesus, etc. (Cho Wha Soon, "Let the Weak Be Strong: A Woman's Struggle for Justice," 1988.)

And today I was reading a book called "The Song," part of a trilogy of "The Singer," "The Song," and "The Finale" by Calvin Miller. These are allegorical stories that explain Jesus' life and then how Christians can live like Jesus. They're really cool--you should read them. They're written almost in the form of poetry, and the flow of the words and the imagery is amazing. Anyway, so the devil comes to this Christian (although they have different names, it being an allegory), and has changed forms. No longer is he "World-hater," this being that everyone knows is evil and whom they fear because of his evil power, but now he is "Sarcon," he is beautiful, he is the ideal person, he knows science and trusts reason, and people are drawn to him because they can understand what he's saying--as opposed to the Christian message. Instead of loving something outside themselves, Sarcon teaches people to love themselves and to try to reach some ideal. Knowledge is the ideal, and science will get them there, because if they just figure out one more thing they'll be able to unlock the secrets of the universe. This is a form of trying to be like God--not that science is evil in itself, but the desire to know everything so that we can be in control, this is idolatry.

So I wonder if perhaps "the devil" has changed forms in Western culture. Instead of being a personified being who we could easily avoid, evil has become amorophous--just the basic desire for power and control, knowledge that will keep us from death, understanding that will keep others subjected to us. If people were possessed by demons they would know there was evil out there. But they're being sneakier--with subtlties we can't quite grasp we are influenced to desire power, recognition, control, love, on our own steam.

I'm not sure if there is no personified devil, or if there is. I'm not sure if there are demons. But I know that there is evil, that sometimes I'm taken with an inane desire to do something that I know is stupidly hurtful or wrong, that sometimes I don't want to do what I know would draw me closer to God who is Life, and whether this is just me and my own stupid human nature or whether this is a personified devil doesn't really matter much. But I'm not throwing out the idea of a personalized devil just yet, because I've had experiences where there's a feeling of deep, unexplainable darkness, and I can't forget the power this has. But thankfully, amazingly, God's power is greater.

I pledge to be in this Lamb's War, even if it takes suffering and death, even when I'm scared, even when I'd rather do something more "respectable." Who's with me?

I will work on the next two points that QuakerK makes on Quaker Glimmerings, because they go together:

I will work on the next two points that QuakerK makes on Quaker Glimmerings, because they go together: