For systematic theology this week we read "God and Human Suffering: An Exercise in the Theology of the Cross" by Douglas John Hall. I thought it was an excellent book (although I didn't get to read ALL of it, but I would have if I had been physically able to!). Hall emphasizes the fact that suffering does exist, that God doesn't encourage it, but that suffering does in a way help us to grow.

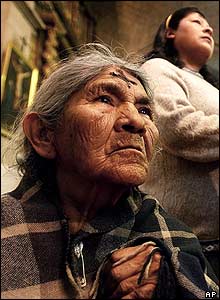

As my precept (small group class) leader wisely stated, his theory works well for those of us in the "first world" because it reminds us of the reality of suffering and our need to admit it and live in it, but not so well for "two-thirds world" people. Hall's point isn't that we should tolerate and stay in our suffering, but the conclusions he draws of our need to face into the reality of suffering speak more to the condition of "first world" avoidance of suffering but continue to experience emotional/psychic/spiritual suffering, than to those who undergo physical suffering on a regular basis.

Hall brings up the important point that in more developed countries today, we tend to ignore suffering and to believe (in a modernist sort of way) that all suffering can and will be eventually overcome by technology. Sometimes we have to live with suffering right now, but that's not as it should be because we should be able to figure out how to get rid of that pain. But Hall reminds us that not all stories used to have a happy ending. In Hebrew Scripture and in Greek tragedy, lament and tragic endings were an important part of life that needed to be expressed and dealt wtih. Now we tend to ignore the fact that we're suffering.

This is easy to do. I don't "suffer" on a regular basis: I get enough food, I have plenty of clothes, I don't have much money but I have enough for what I need and for a few extras here and there. I have the luxury of being in school, taking the time to be trained academically, to sit around thinking all the time. I will inevitably endure suffering as people I know die, and I've experienced emotional suffering in the divorce of my parents and other broken relationships. Sometimes I suffer from being disconnected from the natural world too long and need to get some sun.

I also suffer from lack of community, which I think is a huge one in American culture. I have a great family and network of friends at home, and I'm beginning to develop one here, but it's not the same organic, interdependent community people lived in for centuries. (Of course both ways have their pros and cons, but that's another post for another day...) There is a definite sense of our independence becoming chains of isolation.

These are the kinds of things middle class Americans generally suffer, I think. Two things strike me about this: 1) as Christians, are we really following Jesus if we're not suffering? God doesn't invite suffering on us, but says it will occur if we're being disciples of Christ; 2) although these things don't feel like they can even compare to others' suffering, it is still suffering and I agree with Hall that it would be better if we could admit it as such, learn from it, and be able to empathize with others when they suffer.

Second thought first: Hall says that by denying suffering we are repressing those feelings inside us, therefore numbing us to pain in ourselves and others. If we're not able to recognize our own suffering we can't recognize it in others and relate to them. We also look for someone to villify, because we need a distraction--we need to see how bad someone else is so that we forget about our own shortcomings (hence the Iraq war???). So acknowleding our own suffering not only helps us become more whole people, but helps us build stronger and more empathetic communities, even with our enemies.

First thought: OK, so we aren't supposed to invite suffering--Hall is very clear that Christianity isn't masochistic. But we aren't supposed to shun it, either. Instead we're to listen to God, do what we hear, and be willing to suffer the consequences out of joy for being part of God's plan. This will automatically anger those in power, hence persecution and suffering, but it ultimately shows up the evil of unjust social institutions, etc. and allows the world to witness the transformative power of God in our lives.

For me the idea of suffering is something I've been thinking about a lot for several years. Why does the American church not suffer? Is that a positive thing--because we've created a government that is more fair than ones that persecute religions? Or is it because we're afraid to suffer and aren't willing to radically follow God's will, so we don't rock the boat enough to spark persecution?

I wonder this especially about Quakers. I don't remember if I wrote this on another blog posting earlier, but I often think about the fact that Quakers are generally seen by American culture as a great religion. Now we feel like we have to live up to that reputation, and so we're bound by our desire for popularity. Instead, I think we should wonder and really seek out what it is that God is calling us to as a community, and do that--even if it's unpopular. Let God first, and history, be the judge of whether it was a good idea or not.

I'm challenged to step out more in faith for action--as I've been kind of preoccupied with in the last few days' postings, I suppose. What does it mean in my life that faith is a verb, not a noun--that it's a lifestyle not a possession? How can I act out my faith even now, in the midst of an ultra-Christian community? I think the biggest thing I'm being called to lately is spaciousness...trusting that everything that needs to get done will get done, but I need to hang out with God alone more often. I can't expect to know what God's calling me to if I don't intentionally listen...

This means suffering in the form of giving up my own control of my schedule and fears about not having time to get enough done, setting aside my own priorities to follow God. Blogging helps with that process--it helps me contemplate what I'm learning and gives me a virtual community to share it with, but I also need the times of silent meditation.

Are there things you're feeling drawn to that would require a certain amount of suffering on your part?

Friday, March 31, 2006

Thursday, March 30, 2006

2/3 of the semester blues

Today...I'm wondering what in the world I'm doing in school. It seems to be a recurring theme about 9-10 weeks into each semester. So I have now new break-through thoughts to share, and all I'm doing is trying to memorize Hebrew.

But since I haven't gotten to responding to many of your comments for a while I'll focus on that, and hopefully be a little more inspired tomorrow!

But since I haven't gotten to responding to many of your comments for a while I'll focus on that, and hopefully be a little more inspired tomorrow!

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

faith

Today I was reading a book about Matthew, called "The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew" by Ulrich Luz. One part I was reading talks about true faith being characterized by understanding--over and over throughout the gospels Jesus says, "Those who have ears to hear, let them hear," basically meaning that those to whom the Spirit opens up Jesus' words will understand. So faith is about hearing and understanding, but Luz says, "understanding is not just an intellectual act." It's not enough just to hear the truth and understand it intellectually. It's not enough just to think something's a good idea. Instead, true faith shows that it understands by acting on its knowledge.

I think this is really true. It made me think of learning new things, and how I can understand them as I learn them but then completely forget them. It isn't until I have to do something with that learning that I know whether or not understood it fully. For example, learning Hebrew. I understand the lectures as they are given, it makes sense. But then when I go home and try to do the homework I have to check the book over and over to figure it all out again. I've understood, but it hasn't become a part of my life, of who I am. I currently can't form a Niphal (a Hebrew verb form) participle and show its differences from a Niphal perfect, and until I can I haven't truly understood the Niphal paradigm.

It's the same with faith. I think nonviolent resolution to conflict is the best way. I talk about it a lot. I support groups that work on nonviolence. But how much do I actually DO to work for nonviolent resolution to conflicts?

Luz also says of Matthew, "Faith is mingled in doubt....Faith is expressed in prayer. Prayer is a cry for God's help, at once encompassing trust and desperation. Faith, for Matthew, is not simply a permanent possession...." Here he is talking about Peter's attempt to walk on water with Jesus in Matthew 14. Peter has the courage to attempt this crazy thing, he steps out of the boat, he walks a few steps--and then he freaks out. Suddenly he realizes what he's doing, that this is crazy, that it's impossible to walk on water, and he starts to sink. But he cries out, "Save me, Lord!"

Luz also says of Matthew, "Faith is mingled in doubt....Faith is expressed in prayer. Prayer is a cry for God's help, at once encompassing trust and desperation. Faith, for Matthew, is not simply a permanent possession...." Here he is talking about Peter's attempt to walk on water with Jesus in Matthew 14. Peter has the courage to attempt this crazy thing, he steps out of the boat, he walks a few steps--and then he freaks out. Suddenly he realizes what he's doing, that this is crazy, that it's impossible to walk on water, and he starts to sink. But he cries out, "Save me, Lord!"

I like this depiction of faith. It's kind of scary, because it's not the nice little neatly packaged "salvation" that sounds so easy--say a prayer and you're in--but instead it's a daily, moment-by-moment struggle to stay focused on God. There's no assurance that at any moment I might not start to sink. But there is assurance that I can cry out to God in my moments of doubt--and this is what faith is all about. It's about living out the things we're called to, even when they're scary and crazy, and being willing to admit our doubt and fear.

I want to be the kind of person who hears and understands--truly understands, by putting my faith into practice. I want to be the kind of person who responds with honest prayers of desperation and doubt. I want to listen well--which we as Quakers definitely try to do--and then go out and act, continuing to listen all the way.

I think this is really true. It made me think of learning new things, and how I can understand them as I learn them but then completely forget them. It isn't until I have to do something with that learning that I know whether or not understood it fully. For example, learning Hebrew. I understand the lectures as they are given, it makes sense. But then when I go home and try to do the homework I have to check the book over and over to figure it all out again. I've understood, but it hasn't become a part of my life, of who I am. I currently can't form a Niphal (a Hebrew verb form) participle and show its differences from a Niphal perfect, and until I can I haven't truly understood the Niphal paradigm.

It's the same with faith. I think nonviolent resolution to conflict is the best way. I talk about it a lot. I support groups that work on nonviolence. But how much do I actually DO to work for nonviolent resolution to conflicts?

Luz also says of Matthew, "Faith is mingled in doubt....Faith is expressed in prayer. Prayer is a cry for God's help, at once encompassing trust and desperation. Faith, for Matthew, is not simply a permanent possession...." Here he is talking about Peter's attempt to walk on water with Jesus in Matthew 14. Peter has the courage to attempt this crazy thing, he steps out of the boat, he walks a few steps--and then he freaks out. Suddenly he realizes what he's doing, that this is crazy, that it's impossible to walk on water, and he starts to sink. But he cries out, "Save me, Lord!"

Luz also says of Matthew, "Faith is mingled in doubt....Faith is expressed in prayer. Prayer is a cry for God's help, at once encompassing trust and desperation. Faith, for Matthew, is not simply a permanent possession...." Here he is talking about Peter's attempt to walk on water with Jesus in Matthew 14. Peter has the courage to attempt this crazy thing, he steps out of the boat, he walks a few steps--and then he freaks out. Suddenly he realizes what he's doing, that this is crazy, that it's impossible to walk on water, and he starts to sink. But he cries out, "Save me, Lord!"I like this depiction of faith. It's kind of scary, because it's not the nice little neatly packaged "salvation" that sounds so easy--say a prayer and you're in--but instead it's a daily, moment-by-moment struggle to stay focused on God. There's no assurance that at any moment I might not start to sink. But there is assurance that I can cry out to God in my moments of doubt--and this is what faith is all about. It's about living out the things we're called to, even when they're scary and crazy, and being willing to admit our doubt and fear.

I want to be the kind of person who hears and understands--truly understands, by putting my faith into practice. I want to be the kind of person who responds with honest prayers of desperation and doubt. I want to listen well--which we as Quakers definitely try to do--and then go out and act, continuing to listen all the way.

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

neither protestant or catholic

Yesterday I wrote about the liberation theology of Gutierrez, and I finished that today then read portions of the Vatican II documents for my church history class. We are reading "Apostolate of the Laity" and "Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy."

In many ways I really appreciate Catholicism. There's something to be said for a united "catholic" church, and wouldn't it be easier if one person could tell us what God was saying to the world? I appreciate that Catholicism in the last fifty years or so has produced a huge number of liberation and feminist theologians, and that the Catholic church has struggled to lovingly fit those perspectives into its tradition (less so the feminist position, but that's another story). I appreciate the thought of continuing a tradition that's been handed down for almost two thousand years. It lends it a weightiness that can't come from a single lifetime. I appreciate the willingness in the Vatican II documents to take a fresh look at the traditions, be willing to let go of outdated ones that don't have to do with faith directly, and stand their ground on ones they find important. I can definitely respect that, and I think other denominations could learn much from this kind of maturity (not least Quakerism, perhaps).

At the same time, it's odd to me that liberation theology can come out of such a religion. In the "Apostolate of the Laity," there is all this emphasis on how everyone is unified in the body of the Church, everyone is equal, special favor should be shown to the poor and the marginalized--and all this is great. It says that it is the Christian's duty to look out for the lowly of society and to do works of mercy and charity out of the overflowing of the love of God in our lives. This I can agree with.

But then it gets into things about how it is only the responsibility of the priests to administer Christ to the world in the form of the Eucharist, and that this is the most important way Christians can come into contact with God in the world. And if Catholics want to be part of associations for doing good, that's excellent, but they have to be under the authority of the church hierarchy. They have to be doing only those things approved by the church hierarchy. And the goal of all of this is to bring people in to the church in order to receive the sacraments, which are their only way to get to God.

How did liberation theology come out of this context, I wonder? How can people talk about the equality of all, and at the same time continue believing in and enforcing a hierarchy between people and God? Their documents say expressly that the poor and marginalized have something important to teach the church--and yet they are on the lowest rung of the Catholic ladder, not just society's. And yet, the Catholic church is supporting this movement and encouraging liberation theology.

Plus, the more I learn about classic Protestant theology the more I find Quakerism really has a lot in common with Catholics (and especially Anabaptists, of course). Protestants generally emphasize that it is faith, not our works, that save us. I agree--it is faith that leads us to God, and nothing we do can cause God to offer us grace. But at the same time, if we are only confessing with our mouth that we believe this stuff, and not acting out of the spirit of love, joy, peace, etc., it's worthless!

Recently in one of my classes I learned that in John, the noun for "faith" is never used. Instead, John uses the verb for "faith," meaning faith isn't something, a possession or acquisition. Instead it is something you do. It takes action and life. Protestants would say yes, you do the action of choosing to believe. Here I'm more in line with the Catholics, who emphasize the need to act out our faith in love for our neighbors and enemies, for the marginalized, and love is not just a feeling but an active living-out. It is in this way, say Catholics, Anabaptists and Quakers, that love we love God.

In many ways I really appreciate Catholicism. There's something to be said for a united "catholic" church, and wouldn't it be easier if one person could tell us what God was saying to the world? I appreciate that Catholicism in the last fifty years or so has produced a huge number of liberation and feminist theologians, and that the Catholic church has struggled to lovingly fit those perspectives into its tradition (less so the feminist position, but that's another story). I appreciate the thought of continuing a tradition that's been handed down for almost two thousand years. It lends it a weightiness that can't come from a single lifetime. I appreciate the willingness in the Vatican II documents to take a fresh look at the traditions, be willing to let go of outdated ones that don't have to do with faith directly, and stand their ground on ones they find important. I can definitely respect that, and I think other denominations could learn much from this kind of maturity (not least Quakerism, perhaps).

At the same time, it's odd to me that liberation theology can come out of such a religion. In the "Apostolate of the Laity," there is all this emphasis on how everyone is unified in the body of the Church, everyone is equal, special favor should be shown to the poor and the marginalized--and all this is great. It says that it is the Christian's duty to look out for the lowly of society and to do works of mercy and charity out of the overflowing of the love of God in our lives. This I can agree with.

But then it gets into things about how it is only the responsibility of the priests to administer Christ to the world in the form of the Eucharist, and that this is the most important way Christians can come into contact with God in the world. And if Catholics want to be part of associations for doing good, that's excellent, but they have to be under the authority of the church hierarchy. They have to be doing only those things approved by the church hierarchy. And the goal of all of this is to bring people in to the church in order to receive the sacraments, which are their only way to get to God.

How did liberation theology come out of this context, I wonder? How can people talk about the equality of all, and at the same time continue believing in and enforcing a hierarchy between people and God? Their documents say expressly that the poor and marginalized have something important to teach the church--and yet they are on the lowest rung of the Catholic ladder, not just society's. And yet, the Catholic church is supporting this movement and encouraging liberation theology.

Plus, the more I learn about classic Protestant theology the more I find Quakerism really has a lot in common with Catholics (and especially Anabaptists, of course). Protestants generally emphasize that it is faith, not our works, that save us. I agree--it is faith that leads us to God, and nothing we do can cause God to offer us grace. But at the same time, if we are only confessing with our mouth that we believe this stuff, and not acting out of the spirit of love, joy, peace, etc., it's worthless!

Recently in one of my classes I learned that in John, the noun for "faith" is never used. Instead, John uses the verb for "faith," meaning faith isn't something, a possession or acquisition. Instead it is something you do. It takes action and life. Protestants would say yes, you do the action of choosing to believe. Here I'm more in line with the Catholics, who emphasize the need to act out our faith in love for our neighbors and enemies, for the marginalized, and love is not just a feeling but an active living-out. It is in this way, say Catholics, Anabaptists and Quakers, that love we love God.

Monday, March 27, 2006

liberation theology: unity not uniformity

In my church history class we've made it to the twentieth century. Now, there are many things not to be proud of in twentieth century church history, but there are some to be proud of as well. One of those is liberation theology. We're not reading much for my theology class (although apparently next semester for theology we'll have profs who are more interested in liberation theology, which is nice), but at least we're reading some in church history. This week we're reading the introduction to Gustavo Gutierrez's "A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation."

In my church history class we've made it to the twentieth century. Now, there are many things not to be proud of in twentieth century church history, but there are some to be proud of as well. One of those is liberation theology. We're not reading much for my theology class (although apparently next semester for theology we'll have profs who are more interested in liberation theology, which is nice), but at least we're reading some in church history. This week we're reading the introduction to Gustavo Gutierrez's "A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation."I really like his perspective on liberation theology. He's talking about balancing the themes of love and liberation, freedom for all people, with the admonition to remain focused on the fact that it is from the teaching of Christ--and therefore the Bible and the God of the Hebrew and Christian scriptures--out of which this doctrine has arisen. I'm glad (I think I'm glad, anyway...) it's not just Quakers that struggle with retaining this balance. It seems like so many Friends fall off this tight-rope one direction or the other so easily. But it is from the overwhelming power of liberation through Life-which-has-overcome in the life and teaching of Jesus that the power of our doctrine of peace and justice gets its meaning. This is where the early Quakers got the doctrine from, and it's the spring out of which I attempt to live in as just and peaceful a manner as I can.

This does not mean, however, that we all have to use the same language to describe what we're doing, and that's something else I appreciate about Gutierrez's piece that we're reading. He suggests that theology needs to be created out of the context in which the people who practice it are embedded. So when Christianity was brought to Latin America and church leaders attempted to cause it to continue in the form which had developed in its European setting, it became empty--a bunch of disconnected ideas with no meaning in their Latin American context. Until those in Latin America began to make Christian theology their own, to see the strong emphasis in the Christian message for the poor and marginalized, until they saw their own situation and lifted their own voices to feel and share this message, it was meaningless for that group of cultures.

Now they are speaking a prophetic word to the world, a word that says, "Listen! Hear God through the disenfranchised." This is the gospel message, in their own language, a message that is for the whole world but again must not be applied directly to every other context. Instead it must be molded to the context which receives it, while the truth of the message still remains intact. This is where the problem lies, because how do we know we're being true to the message unless we speak the same "language" (and I'm not really talking about Spanish here)?

Gutierrez says, "Authentic universality does not consist in speaking precisely the same language but rather in achieving a full understanding within the setting of each language." It's not that we all have to speak and act exactly the same way--this is uniformity. But instead we are called to take the time to understand one another, and see the Light of God in one another, and to allow that Light to inform how we live in our own context. This is true unity, a universality that allows for diversity and truth.

One of my favorite singer/songwriters, David Wilcox (who I've quoted on here before), has a song about listening for understanding. When he explained it in a concert (and on his Live Songs and Stories CD) he said that this unity is like having a disagreement with someone you love: if you take the time to listen, sometimes you get so far into their perspective that you can hardly remember what your own argument was! He says he loves it when that happens--it's like a figure-ground picture. "Same dots, same data, different picture!"

Kinda' like the blind men and the elephant...

Sunday, March 26, 2006

thoughts about CPTers' rescue

It's been a few days since this happened so probably most of you know by now that three of the Christian Peacemaker Teams members who were kidnapped last November in Iraq were rescued on Thursday. (The fourth, Tom Fox, was found dead a couple weeks ago.) The three men were rescued by a Multi-National Force, made up, it sounds like, mainly of armed forces from their home countries of the UK and Canada.

It's been a few days since this happened so probably most of you know by now that three of the Christian Peacemaker Teams members who were kidnapped last November in Iraq were rescued on Thursday. (The fourth, Tom Fox, was found dead a couple weeks ago.) The three men were rescued by a Multi-National Force, made up, it sounds like, mainly of armed forces from their home countries of the UK and Canada.I'm incredibly grateful that they were rescued, that they are alive, that they seem to have been treated well in captivity, and that the MNF who rescued them honored CPT's peace stance by not using violence in the rescue operation. You can read more about this on CPT's website, where there are links to news articles and statements from the men who were captured and from CPT.

Apparently the CPTers are being accused of not showing gratitude for their rescue to the army personnel who released them. I think that's a hard balance, because although I'm sure they are grateful to be free, they and CPT asked repeatedly for the armed forces not to be involved in this situation. So I appreciate the statement they issued:

I do not believe that a lasting peace is achieved by armed force but I pay tribute to [the soldiers] courage and thank those who played a part in my rescue.... There's a real sense in which you are interviewing the wrong person. It's the ordinary people of Iraq you should be talking to, the people who have suffered so much over many years and still await the stable and just society they deserve.

Who's working for the release of all those Iraqis who are being detained illegally without charge by the same Multi-National Forces? Are the armed forces continuing to honor the work of CPT as they continue the Iraqi occupation in order to make it less likely that someone would want to capture Westerners?

Nonviolent resolution of conflict is so difficult. It seems so impractical. And yet, these men were released by armed forces in a nonviolent way. The army was challenged to think of a different way to go in and rescue these men than their default of violence, and I think the fact that it was successful says a lot about what's possible with nonviolence. What if in every situation the "army" (or whatever it would be called) would sit down and think about how they might be able to solve the situation other than through the use of force?

Most Christians would say, I think, that most violence is not justifiable and it should only be used as a last resort. But when do we know that it's the last resort? How many nonviolent options have actually been tried in each circumstance? What if we had sent spies into Iraq and taught people about nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience instead of invading their country with weapons? What if we had encouraged and empowered those same people who are leaders of paramilitary factions in Iraq to use nonviolent methods to overthrow the unjust government which was oppressing them? What if the people of Iraq had been given tools to come together and work on their freedom together and to create their own peaceful way?

Perhaps it would have seemingly taken longer. Perhaps lots of innocent people would have died. Perhaps they would have created a new government over which Western governments had less power.

And perhaps it would have taken less time, because this war has already lasted three years and the end is still not in sight. And perhaps innocent people would have died, but their blood would not be on our heads, and their deaths would have been seen as martyrdoms to encourage solidarity and resolve in the hearts of those left behind. And perhaps people should be free to create the form of government that will work best for them, and not be controlled by outside forces that don't take the time to understand their culture...and besides, wouldn't they be more likely to look on our country with favor if we had helped them achieve their own freedom while acknowledging their personhood, rather than not even keeping an accurate count of how many Iraqis die in this conflict every day?

I believe CPT is working to do all this. They have had 120 volunteers in Iraq since the war started, according to their website. With those 120 volunteers they have achieved the release of many illegally detained Iraqis, raised awareness about the abuses going on in Abu Ghraib and other facilities, stayed in the country when almost all other humanitarian aid agencies have left due to danger, and helped form a Muslim Peacemaker Team based on Islam.

What could they do if they had as many individuals involved and committed to the cause of nonviolent conflict resolution as the armed forces have individuals committed to violent conflict resolution? What could CPT do if it had even half, or a quarter of the number involved in the army? Isn't it easier to successfully and lastingly solve a conflict with love than with hate?

Pictures are: 1) Harmeet Sooden & James Loney, 2) Norman Kember, 3) Tom Fox. From CPT website, www.cpt.org

Friday, March 24, 2006

predestination

Today in my systematic theology precept (small group class) we discussed divine Providence, which inevitably (at least from God's perspective--ha!) led to a discussion of predestination. So I've been thinking about predestination and wondering what the official Quaker view is on the matter.

Now, admittedly I haven't read Barclay's Apology all the way through, and I haven't even read the parts I've read for about 6 years, so I don't know for sure if Barclay addresses this issue, but I just found the Apology online and did a search for the world "predistination" and neither of the two places it showed up did it really outline his position, as far as I could tell. I'm not sure if there's a Quaker doctrine on predistination, although I think Quakers are generally not really excited about predestination.

So what's the big deal with predestination? The major question is, does God know ahead of time what everyone will do and what will happen in all of history? And there are tons of subsequent questions. If God knows what will happen, do humans have any free will to choose their actions, or is the fact that God knows the future limiting us to act in the way God foreknows? If not, then is God really omniscient and can God have everything under control, headed toward a specific goal, as the doctrine of Providence says God is doing? And even if we don't think about the doctrine of Providence, if God doesn't know what's going to happen, who's in control and where's the meaning in life? If God foreknows what will happen, is God causing that to happen, or just knowing, and is there a difference?

If God knows what will happen, why does God allow bad things to happen to innocent people, good things happen to people who are not so nice, and allow natural disasters? If God knows what will happen and uses it all for good, does that mean that when people do things that aren't good they are doing the will of God, and if so can they really be held accountable for it?

There are also questions of salvation through faith or works. If we assume a Christian pespective (which I'm sure not all Quakers will do comfortably but bear with me), does God offer salvation to all people? If so, whose fault is it that some accept it and some do not? Is it people's fault for not recognizing God in their lives? Or is it God's fault for not presenting God's self in a way they will accept, when God knows full well that they will not accept God from the experiences they're given? Does God create some people knowing they will not accept God? Why does God even create them in that case? And if God doesn't know who will end up choosing God or not, is God bound to time as we are, or is God able to hide things from God's self until the time comes to know fully, or what? And if we're all presented with the ability to be "saved," and we have to choose it, doesn't that mean that our faith--our own human action--is what saves us rather than the grace of God? (Most Protestants have a huge problem with this part.)

Put in Quaker words, if everyone has the Light of God within, a piece of themselves that can connect with God and others on a spiritual level, then why do some respond ot it and others try to stifle it? If everyone has the Light of God within but some are taught to pay attention to that and nurture it and others are taught the opposite, whose fault is it if someone doesn't respond to that God-spark? The individual's, because they have God's presence right there inside; the community who raised them, for not teaching them better; or God, for not making God's self known in an understandable way?

I don't have any answers for all this, except to say that somehow, I believe that God does have knowledge of what's going to happen, but this knowledge doesn't mean that God causes us to do things. Somehow we still have free will. Somehow God presents God's self to us in a way that each of us can understand if we choose to, and this choosing has to do with the Spirit guiding us to understand as well as our own willingness to be guided by the Spirit. So we do have to take action in accepting God's Light as our inner guide, but God also has freely extended that to us without our deserving it. God is moving the entire universe toward relationship with God, and we have the choice to participate in that or not. God's will will be done, however, whether we cooperate or not.

So that's my stab at this Quaker's doctrine of predestination, and I suppose I could come up with proof-texts from the Bible to support these views, but there has been enough of that in the history of the doctrine of predestination to make anyone sick, so I won't put you through that. Instead hopefully we can allow the Spirit to sift the truth and falsehood for us in each of our beliefs and help us understand this matter more clearly.

Or, more likely, this is just part of the beautiful, paradoxical mystery of our present God that we will never understand...but I think we are to die trying.

Now, admittedly I haven't read Barclay's Apology all the way through, and I haven't even read the parts I've read for about 6 years, so I don't know for sure if Barclay addresses this issue, but I just found the Apology online and did a search for the world "predistination" and neither of the two places it showed up did it really outline his position, as far as I could tell. I'm not sure if there's a Quaker doctrine on predistination, although I think Quakers are generally not really excited about predestination.

So what's the big deal with predestination? The major question is, does God know ahead of time what everyone will do and what will happen in all of history? And there are tons of subsequent questions. If God knows what will happen, do humans have any free will to choose their actions, or is the fact that God knows the future limiting us to act in the way God foreknows? If not, then is God really omniscient and can God have everything under control, headed toward a specific goal, as the doctrine of Providence says God is doing? And even if we don't think about the doctrine of Providence, if God doesn't know what's going to happen, who's in control and where's the meaning in life? If God foreknows what will happen, is God causing that to happen, or just knowing, and is there a difference?

If God knows what will happen, why does God allow bad things to happen to innocent people, good things happen to people who are not so nice, and allow natural disasters? If God knows what will happen and uses it all for good, does that mean that when people do things that aren't good they are doing the will of God, and if so can they really be held accountable for it?

There are also questions of salvation through faith or works. If we assume a Christian pespective (which I'm sure not all Quakers will do comfortably but bear with me), does God offer salvation to all people? If so, whose fault is it that some accept it and some do not? Is it people's fault for not recognizing God in their lives? Or is it God's fault for not presenting God's self in a way they will accept, when God knows full well that they will not accept God from the experiences they're given? Does God create some people knowing they will not accept God? Why does God even create them in that case? And if God doesn't know who will end up choosing God or not, is God bound to time as we are, or is God able to hide things from God's self until the time comes to know fully, or what? And if we're all presented with the ability to be "saved," and we have to choose it, doesn't that mean that our faith--our own human action--is what saves us rather than the grace of God? (Most Protestants have a huge problem with this part.)

Put in Quaker words, if everyone has the Light of God within, a piece of themselves that can connect with God and others on a spiritual level, then why do some respond ot it and others try to stifle it? If everyone has the Light of God within but some are taught to pay attention to that and nurture it and others are taught the opposite, whose fault is it if someone doesn't respond to that God-spark? The individual's, because they have God's presence right there inside; the community who raised them, for not teaching them better; or God, for not making God's self known in an understandable way?

I don't have any answers for all this, except to say that somehow, I believe that God does have knowledge of what's going to happen, but this knowledge doesn't mean that God causes us to do things. Somehow we still have free will. Somehow God presents God's self to us in a way that each of us can understand if we choose to, and this choosing has to do with the Spirit guiding us to understand as well as our own willingness to be guided by the Spirit. So we do have to take action in accepting God's Light as our inner guide, but God also has freely extended that to us without our deserving it. God is moving the entire universe toward relationship with God, and we have the choice to participate in that or not. God's will will be done, however, whether we cooperate or not.

So that's my stab at this Quaker's doctrine of predestination, and I suppose I could come up with proof-texts from the Bible to support these views, but there has been enough of that in the history of the doctrine of predestination to make anyone sick, so I won't put you through that. Instead hopefully we can allow the Spirit to sift the truth and falsehood for us in each of our beliefs and help us understand this matter more clearly.

Or, more likely, this is just part of the beautiful, paradoxical mystery of our present God that we will never understand...but I think we are to die trying.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

resisting as existing

I was reading for systematic theology, and again this week what stood out to me this week was from our book on Jonathan Edwards by Sang Hyun Lee. This week we're talking about the doctrine of divine "Providence"--I didn't even know people use the word "Providence" anymore in the twenty-first century, but I guess there's a whole doctrine about it. The Christian doctrine of Providence basically says that God is working in everything that goes on in the universe in order to bring about a good end, namely, in order to fulfill the covenant of grace begun with humanity (which seems kind of anthropocentric, but that's the doctrine anyway). This brings up a lot of questions, and maybe I'll focus on some of them a different day, but for now I'll just mention them: there's the ever-present "theodicy" question--if God is working for good, why is there so much evil? And if God is working to bring about a certain end, do humans actually have any freedom to choose their own actions? And more questions flow from these lines of thinking.

I was reading for systematic theology, and again this week what stood out to me this week was from our book on Jonathan Edwards by Sang Hyun Lee. This week we're talking about the doctrine of divine "Providence"--I didn't even know people use the word "Providence" anymore in the twenty-first century, but I guess there's a whole doctrine about it. The Christian doctrine of Providence basically says that God is working in everything that goes on in the universe in order to bring about a good end, namely, in order to fulfill the covenant of grace begun with humanity (which seems kind of anthropocentric, but that's the doctrine anyway). This brings up a lot of questions, and maybe I'll focus on some of them a different day, but for now I'll just mention them: there's the ever-present "theodicy" question--if God is working for good, why is there so much evil? And if God is working to bring about a certain end, do humans actually have any freedom to choose their own actions? And more questions flow from these lines of thinking.But what stood out to me was something I read Edwards' struggle with these issues. He was attempting to reformulate the idea of "substance" from Aristotle's idea of "forms," which is basically an archetypal form of perfection and beauty underlying the imperfect things we see and experience. Edwards says instead that substance is getting down to the solid part of things (which he calls "atom" although now we know there are smaller things than atoms)--so you get down to this solid part, where nothing can be divided from it any longer, and that thing-which-cannot-be-divided is "solidity." He says since it can't be divided it's perpetually in the action of resisting division, and it is this resistance to division which defines existence.

Therefore existence is essentially relational, because one can only resist if there's something else, something other, to resist. He says this solidity is God, because God is infinitely indivisible, active and relational. (He explains this, but I don't want to go into the details here, just suffice it to say he has some pretty good arguments.) An important distinction here is that everything solid isn't God exactly (as in pantheism), but that God is the substance that sustains everything. It is God's act of resisting division and destruction that causes existence to continue. This is how God is "Providence," in that God sustains everything and must be present and active, working for the continued existence of everything, in order for anything to exist.

So I thought this was a really interesting thought, and I thought of implications which I'm not sure if Edwards would think followed at all, but it sparked these thoughts anyway. And I'm going to set aside modern physics and chemistry all that, ignore the questions of whether there actually is anything solid and indivisible and not just loads of space between infinitesimal quarks and whatever smaller atomic pieces there are, because I don't know enough about all that to speak intelligently about it, and because for the sake of this thought process I'm going to assume there is something eventually, however small, that is solid and indivisible.

Here's my thought: if existence if the act of resisting destruction and division--basically the act of resisting falling into chaos, does this say anything about the way we should live our lives? Does it extrapolate to a relatively macroscopic level, where because our very atoms are resisting division, we also should live out this resistance in our lives? What would this look like?

I think what Jesus calls us to, what Donald Kraybill and others call the "upside down Kingdom," where the last are first and the first are last, the greatest is the one who serves, no one can enter the Kingdom except as a little child, where we foolishly love people, even our enemies, where we forgive people as many times as they ask it, this is the act of resistance to which our "atoms" call us. This is the acting out of our solidarity with others, our refusal to be separated--divided--by race, class, gender, nation, or culture. This is the sense of substance and solidity which is the paradoxical kernel of truth that can keep our world from spinning into the non-existent divisiveness of chaos and war, fear, hatred, and judgment without mercy which would (and does) threaten the very fabric of our delicately woven world of spacious atoms and microscopic solidity.

But to resist the obvious--what seems easy, what seems solid--the easy way out of hatred and "eye for an eye" revenge, to resist this and see that our solidity, our substance, comes from solidarity and relationship with the Living God who holds all things together and works for good, this is what existence is all about.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

the kingdom of God is within y'all

I was in class today (class title: Theologies of the Gospel Evangelists, translation: the theologies of those who wrote and edited Matthew, Mark, Luke, John and the Gospel of Thomas), and we're currently focusing on Luke.

I was in class today (class title: Theologies of the Gospel Evangelists, translation: the theologies of those who wrote and edited Matthew, Mark, Luke, John and the Gospel of Thomas), and we're currently focusing on Luke.My professor said something I had learned before but forgotten, whcih I thought was important and might help us as Quakers as we think about the "Inner Light." He reminded us that in Luke 17:21 when it says "the Kingdom of God is within you," the Greek for "you" is plural, which of course we can't tell in modern English. What does that say about our faith, I started wondering?

In our culture where we imagine ourselves to be so autonomous, where we think we can get by on our own, or if we're religious, I can get by just me and God, it's hard to imagine what it could mean that "the Kingdom of God is within y'all," as my professor put it. This is an idea that we really started losing in our culture's urbanization and industrialism: living in a city, there's no need to know anyone, and unless you think about it you don't always recognize how much you depend on other people. This cultural pattern had a spiritual effect, and so churches became more individualistic as well: faith became a personal choice, asking Jesus into my heart, or I can believe whatever I want to believe because it's my own business and doesn't affect anyone else. It's a private matter, relegated to the "private sphere" along with family and my real self, where no one else is allowed to interfere.

Quakers do this, too. Often we come to meeting, whether programmed or unprogrammed, sit there for an hour or so, say hello to the people around us and listen respectfully to what others say during worship but pretty much focus on ourselves and our own relationship with God, and then go home. We've nourished our Inner Light, we've done our duty, let's get on with life. (OK, so no one would put it that way and perhaps that's an exaggeration, but I think it shows the kind of attitude many Quakers show even if they would say they act differently.)

I confess I am guilty of this at times. Sometimes I just want to sit in meeting in silence and not have to listen to someone share about something that doesn't pertain to me, or if I'm at a programmed service I don't want to sing such-and-such a song because I don't like the melody, or the theology, or whatever it happens to be. But I sit there and do my duty like a good Friend, I smile at those around me and say hello, and then I go home.

But what then is the point of gathering together? Why have Quakers traditionally seen it as so important to be part of a community of faith? If the Inner Light is sufficient to guide me where I need to go, if the Kingdom of God is within me, what's the point of a community?

I'm not sure where the early Friends got the idea of the Inner Light, although probably it's a conglomerate of John 1 where Jesus is referred to as the Light shining in the darkness but the darkness has not understood it, which Light/Word/Life was present in the beginning with God and was God, and then several passages in John, Luke and Matthew where the Kingdom of God is referred to as being present in the believer. I don't think George Fox or any of the early Friends knew Greek so they may not have picked up on the plural "you," although they spoke King James English so it may have been more distinct to them what was singular and plural, I don't want to look it up right now.

But even though the early Friends talked about an Inner Light, they also stressed the importance of community. They knew the power of God resides in a gathering of people who are faithfully listening to God together and challenging themselves and one another to action. The knew the Kingdom of God is present in the gathered community, not only in the individual.

So I'm challenged by this idea to push away all my American enculturation in this area and to meditate on what it means that the Kingdom of God is present in "y'all." I suppose one could think of it as Luke saying the Kingdom is present in everyone, so you all as individuals have the Kingdom in you, but in that case he could have written you in the singular, so that you would know he was talking to you specifically and as an individual. But instead he wrote "y'all." To me this means the Kingdom of God is present in people acting out of faithful attentiveness to God's "good news" in their midst. I know the idea of "good news" has been hijacked by some who call themselves Christians to just mean "the good news that we get to go to heaven," but Jesus said in Luke 4:18-19 that he had come to bring good news to the poor, to release the oppressed, to make the blind see, and to proclaim the year of the Lord's favor, and he invited those around him to join him in these things.

This is the good news of the Kingdom of God that the early Friends preached and lived. It seems like our autonomy, our idea of the Kingdom of God being in ME, has often kept us of late from being able to live these things out effectively together.

Sunday, March 19, 2006

longing for the spring

It's almost the first day of spring and I'm incredibly ready for it to be here. I pulled my bike out again for the first time since fall the other day--I was so excited! Here in New Jersey it's dry and still kind of cold, sunny but still brown and dead-looking. It's much different from what I'm used to in Oregon, where it's gray and rainy about now, but the grass is green and leaves are probably already coming on, and the evergreens are of course still green. In Oregon I wouldn't be riding a bike yet, but I also wouldn't still feel like everything's dead--there would be early spring flowers and leaves everywhere (although they may have died last week with their freak snow storm!).

It's almost the first day of spring and I'm incredibly ready for it to be here. I pulled my bike out again for the first time since fall the other day--I was so excited! Here in New Jersey it's dry and still kind of cold, sunny but still brown and dead-looking. It's much different from what I'm used to in Oregon, where it's gray and rainy about now, but the grass is green and leaves are probably already coming on, and the evergreens are of course still green. In Oregon I wouldn't be riding a bike yet, but I also wouldn't still feel like everything's dead--there would be early spring flowers and leaves everywhere (although they may have died last week with their freak snow storm!).I have seen a few flowers here already, though! On the bike path there was a strip of daffodils and I stopped and picked some to bring home, and already it feels more like spring. But I was riding my bike to meeting today past three fields of brown stubble with trees brown and barren and wondering if spring is ever going to get here.

There's something incredible about the waiting, though, and I've been trying to enjoy the anticipation and longing, and seeing what it has to teach me. It's a ruminating time, a time of seeming dormancy, a calm before the explosion of new life that will soon come. I notice myself waiting and longing with an aching sense of desire for regeneration in myself, not just in the landscape.

I'm not sure why the year begins on January 1--I think it should begin with spring, because that's when things really become new. I'm much more interested in New Year's resolutions now, and I might actually keep them for a while--like getting exercise, because I can ride a bike!

I never used to really appreciate the seasons much, just kind of experienced them as they came. But now I notice them (maybe because there are actually four seasons here), and the rhythm of the seasons reminds me of the embodied person that I am, who needs change, new life, death, times of waiting, times of energy, harvest and planting and fallowness.

In Hebrew we translated Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 the other day (which was nice because it's very repetetive so it wasn't very hard!), and it reminded me of these seasons and the patient cycle of it all. So here's Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 (Cherice's version) to meditate on as we await the spring.

For everything there is an appointed time, and a season for each pleasure:

a season for bearing, and a season for dying;

a season for planting, and a season for uprooting plants;

a season for killing, and a season for healing;

a season for breaking down, and a season for building up;

a season for weeping, and a season for laughing;

a season for lamenting, and a season for skipping joyfully;

a season for casting stones, and a season for gathering stones together;

a season for embracing, and a season for being distant from embracing;

a season for seeking, and a season for losing;

a season for keeping, and a season for throwing away;

a season for rending, and a season for sewing together;

a season for being silent, and a season for speaking;

a season for love, and a season for hate;

a season for battle, and a season for peace.

Thursday, March 16, 2006

God imagining God's self to us

Paul made a good point in his comment to my last post: what do I mean by "God imagining God's self to us," and where did I get that from? I kind of just tacked that onto the end there and didn't explain very well (because I gave myself a blogging time limit and it was about to expire! =) So I'll see if I can explain it here.

I think "God imagining God's self to us" is a bona fide Cherice-ism, but it does have some influence from other theologians and the Bible. At first I thought of us imagining what God is like, but then realized if we're doing that, we're just making God into who we want him/her to be. But if God is imagining God's self to us, we can get a picture or metaphor for who God is that comes from God. It may be difficult to discern when it's me imagining and when God is imagining to me, but hopefully with practice and trust we can figure it out at least some of the time.

One of the ways many people think of the "Image of God" humans are said to have is that our creativity is the way we are like God. It is a way we connect with God, and a gift of God's character that only humans (at least of creatures of the Earth, as far as we can discern) have been given. I even read a book last term that suggested that creativity is God (written by a former Mennonite, now a philosopher of religion) called "In the Beginning...Creativity," by Gordon Kaufman. It was an interesting hypothesis, and I agree with him that God is the essence of creativity, but God is also personal, an actual being--not just a vague concept of creativity. But his idea is helpful: through the medium of creativity we can know God better, and our creativity is an important way that we are like God.

This week in systematic theology we read part of Sang Hyung Lee's book "The Theology of Jonathon Edwards." I didn't really expect to be a big Jonathon Edwards fan, after reading "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" in high school American history class, but apparently that's not his normal theology (that was more influenced by George Whitefield and the revivalist preachers--it was Edwards getting on the bandwagon of popular religion). Anyway, what we read for this week had to do with Edwards' idea of creation. It would take too long to explain how he got to this point, so I won't bore you with a recapitulation of Lee's recapitulation of Edwards...but suffice it to say that Edwards thinks that because God's essence is about relationship and self-communication, one of the major reasons that God created the universe was to communicate God's whole self in time and space.

What this has to do with the topic of God imagining God's self to us is that Edwards sees God doing this self-communication as a repetition in time which happens through the human imagination. God obviously does not repeat God's self in actuality--God is not creating another God. But what God is doing is revealing God's self to us, and through our perception of that in our minds, through our remembrance of God's revelation in our imaginations, God is repeated in time and space and able to communicate God's self only through the perception of intelligent beings that are other-than-God. God's actual self is still the same and another actual God doesn't come into being, but the idea of God is KNOWN, and it is this knowing which is part of who God is in the world.

So that's one basis for God imagining God's self to us. God "needs" people to perceive God through our minds and imaginations in order for God's self to be communicated (at least God set up a system that requires people, although there probably could have been other ways for this to happen). If people only perceive God in the forms of Father, Son and Holy Spirit is God able to fully communicate the fullness of who God is to us?

Another foundation for this idea is imagery in the Bible. There are plenty of examples of God utilizing people's imaginations in order to impart truths to them they probably would not have thought of or grasped otherwise. The parables of Jesus are a good example of this: Jesus often prefaced his parables in Matthew, Mark and Luke by saying, "The Kingdom of God/Heaven is like..." Many times an explanation for the parable's meaning is not given, and the hearer is forced to think about--to imagine--how the Kingdom of God could be like a man with two sons, a woman who lost her coin, a shepherd, etc. How do these metaphors help us see a bigger picture of who God is?

In these parables Jesus shows us examples of people similar to the experience of those who would be listening to him. Are we still supposed to use those examples only as we seek to understand God, or are we able to follow Jesus' example and see metaphors for God in the people and situations in our own culture? Might God continue to use our imaginations to show us who God is like that connects with our own experience?

Other examples from the Bible include those who had visions of God or God's word, like Isaiah seeing God in heaven and volunteering for the mission as God's mouthpiece to Israel, or God asking Abr(ah)am to count how many stars there were in the sky or sand in the sea and to imgaine that God would make his descendents as numerous as they; God telling Elijah that God was going to show God's self to him and Elijah imagining God was in the earthquake or wind or fire but God shows up in the still, small voice in Elijah's mind; God using the analogy of Hosea's marriage to Gomer to show Israel a metaphor for their relationship to God; and many other examples I won't go into now.

The Elijah story is important because Elijah tried to use his own imagination to guess what God was like, but God showed up in a way completely other than what he'd expected, but completely recognizable as God. This is good news because if we wait long enough, our own active imaginations will let go, and God can come through as God is.

As a modern-day example of this idea, the other day my husband told me about a vision he had where God showed him an image of centeredness that he wouldn't have thought of on his own. He tried to hijack the vision, trying to guide it or guess where it was going, but when he allowed God to imagine God's self for him he received a vision of God unlike his own imagination, although incorporating his own experiences and knowledge. This new idea of God was completely Other from himself and his own thoughts, and yet completely intimate and integrated with who he is as an individual.

So I think God uses our imaginations to help us understand more about who God is. Sometimes we get in the way and try to decide who God's going to be, but our imaginations can be an important tool to help us see God in new ways. I think it's important to be held accountable by the Bible and our communities to make sure the images we receive are consistent with God as revealed through history and to others, but at the same time, I think God shows us God's self in ways that are uniquely important for us specifically and don't necessarily fit very well into historical molds. This is not to say that God will be vastly different from the God present to others in history, but that the image we receive may be different from any we have ever heard of before (such as F/friends of mine who have received images of God as the Holy Goose, a guy in Converse, a cat, a butterfly, etc.)

I think "God imagining God's self to us" is a bona fide Cherice-ism, but it does have some influence from other theologians and the Bible. At first I thought of us imagining what God is like, but then realized if we're doing that, we're just making God into who we want him/her to be. But if God is imagining God's self to us, we can get a picture or metaphor for who God is that comes from God. It may be difficult to discern when it's me imagining and when God is imagining to me, but hopefully with practice and trust we can figure it out at least some of the time.

One of the ways many people think of the "Image of God" humans are said to have is that our creativity is the way we are like God. It is a way we connect with God, and a gift of God's character that only humans (at least of creatures of the Earth, as far as we can discern) have been given. I even read a book last term that suggested that creativity is God (written by a former Mennonite, now a philosopher of religion) called "In the Beginning...Creativity," by Gordon Kaufman. It was an interesting hypothesis, and I agree with him that God is the essence of creativity, but God is also personal, an actual being--not just a vague concept of creativity. But his idea is helpful: through the medium of creativity we can know God better, and our creativity is an important way that we are like God.

This week in systematic theology we read part of Sang Hyung Lee's book "The Theology of Jonathon Edwards." I didn't really expect to be a big Jonathon Edwards fan, after reading "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" in high school American history class, but apparently that's not his normal theology (that was more influenced by George Whitefield and the revivalist preachers--it was Edwards getting on the bandwagon of popular religion). Anyway, what we read for this week had to do with Edwards' idea of creation. It would take too long to explain how he got to this point, so I won't bore you with a recapitulation of Lee's recapitulation of Edwards...but suffice it to say that Edwards thinks that because God's essence is about relationship and self-communication, one of the major reasons that God created the universe was to communicate God's whole self in time and space.

What this has to do with the topic of God imagining God's self to us is that Edwards sees God doing this self-communication as a repetition in time which happens through the human imagination. God obviously does not repeat God's self in actuality--God is not creating another God. But what God is doing is revealing God's self to us, and through our perception of that in our minds, through our remembrance of God's revelation in our imaginations, God is repeated in time and space and able to communicate God's self only through the perception of intelligent beings that are other-than-God. God's actual self is still the same and another actual God doesn't come into being, but the idea of God is KNOWN, and it is this knowing which is part of who God is in the world.

So that's one basis for God imagining God's self to us. God "needs" people to perceive God through our minds and imaginations in order for God's self to be communicated (at least God set up a system that requires people, although there probably could have been other ways for this to happen). If people only perceive God in the forms of Father, Son and Holy Spirit is God able to fully communicate the fullness of who God is to us?

Another foundation for this idea is imagery in the Bible. There are plenty of examples of God utilizing people's imaginations in order to impart truths to them they probably would not have thought of or grasped otherwise. The parables of Jesus are a good example of this: Jesus often prefaced his parables in Matthew, Mark and Luke by saying, "The Kingdom of God/Heaven is like..." Many times an explanation for the parable's meaning is not given, and the hearer is forced to think about--to imagine--how the Kingdom of God could be like a man with two sons, a woman who lost her coin, a shepherd, etc. How do these metaphors help us see a bigger picture of who God is?

In these parables Jesus shows us examples of people similar to the experience of those who would be listening to him. Are we still supposed to use those examples only as we seek to understand God, or are we able to follow Jesus' example and see metaphors for God in the people and situations in our own culture? Might God continue to use our imaginations to show us who God is like that connects with our own experience?

Other examples from the Bible include those who had visions of God or God's word, like Isaiah seeing God in heaven and volunteering for the mission as God's mouthpiece to Israel, or God asking Abr(ah)am to count how many stars there were in the sky or sand in the sea and to imgaine that God would make his descendents as numerous as they; God telling Elijah that God was going to show God's self to him and Elijah imagining God was in the earthquake or wind or fire but God shows up in the still, small voice in Elijah's mind; God using the analogy of Hosea's marriage to Gomer to show Israel a metaphor for their relationship to God; and many other examples I won't go into now.

The Elijah story is important because Elijah tried to use his own imagination to guess what God was like, but God showed up in a way completely other than what he'd expected, but completely recognizable as God. This is good news because if we wait long enough, our own active imaginations will let go, and God can come through as God is.

As a modern-day example of this idea, the other day my husband told me about a vision he had where God showed him an image of centeredness that he wouldn't have thought of on his own. He tried to hijack the vision, trying to guide it or guess where it was going, but when he allowed God to imagine God's self for him he received a vision of God unlike his own imagination, although incorporating his own experiences and knowledge. This new idea of God was completely Other from himself and his own thoughts, and yet completely intimate and integrated with who he is as an individual.

So I think God uses our imaginations to help us understand more about who God is. Sometimes we get in the way and try to decide who God's going to be, but our imaginations can be an important tool to help us see God in new ways. I think it's important to be held accountable by the Bible and our communities to make sure the images we receive are consistent with God as revealed through history and to others, but at the same time, I think God shows us God's self in ways that are uniquely important for us specifically and don't necessarily fit very well into historical molds. This is not to say that God will be vastly different from the God present to others in history, but that the image we receive may be different from any we have ever heard of before (such as F/friends of mine who have received images of God as the Holy Goose, a guy in Converse, a cat, a butterfly, etc.)

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

secret life of bees

I finished reading the book "The Secret Life of Bees" by Sue Monk Kidd the other day.

I finished reading the book "The Secret Life of Bees" by Sue Monk Kidd the other day.Yesterday's post was kind of heavy, and I don't want to forget all that, but maybe sometimes being accountable to the responsibility left us by martyrs is following our passions and working for God's glory in every area we are involved in. That's why I tend to write posts about books I read and movies I see--because even these expereinces are "sacraments," places where God can and does speak to us and call us to transformation.

So about this book...

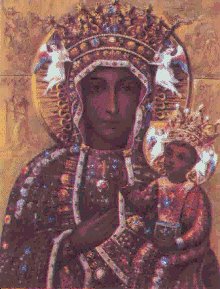

It's a story about a young girl coming-of-age, of course, as many books are. She lives in the South in the '60s. The story deals with spirituality, racism, grief and loss, joy and love. Lily, the main character, lost her mother when she was little and has only a few possessions left that belonged to her mother. One is a picture of the Black Madonna, and she is drawn to this picture--she doesn't know why. She knows it's strange, because Mary's supposed to be white, connoting purity and virginity. But this was her mother's. On the back her mother wrote the name of a town, and when Lily is forced to run away she heads for that town.

It's a story about a young girl coming-of-age, of course, as many books are. She lives in the South in the '60s. The story deals with spirituality, racism, grief and loss, joy and love. Lily, the main character, lost her mother when she was little and has only a few possessions left that belonged to her mother. One is a picture of the Black Madonna, and she is drawn to this picture--she doesn't know why. She knows it's strange, because Mary's supposed to be white, connoting purity and virginity. But this was her mother's. On the back her mother wrote the name of a town, and when Lily is forced to run away she heads for that town.In the story she meets up with a group of African American women who keep bees, who teach Lily how to live and love and grieve and be honest and to connect with her spirituality.

It's an amazing book, and I've also read another one by Sue Monk Kidd called "Dance of the Dissident Daughter," which isn't a novel but tells her story and her thoughts as she found herself in a fundamentalist Christian environment and came to know God as her Mother, using feminine imagery and symbolism. I used that one as a source for a couple of papers I wrote last term.

It's an amazing book, and I've also read another one by Sue Monk Kidd called "Dance of the Dissident Daughter," which isn't a novel but tells her story and her thoughts as she found herself in a fundamentalist Christian environment and came to know God as her Mother, using feminine imagery and symbolism. I used that one as a source for a couple of papers I wrote last term.Now, the "religion" the women in "The Secret Life of Bees" is not exactly "Christian," they're worshiping Mary. (One could say that's as Christian as Catholicism, but I think if you ask most Catholics they'll tell you they're not actually worshiping Mary, just praising her for being the mother of Christ. The women in the story are actually worshiping her.) I don't think we should worship other people, but at the same time, what are women supposed to do? Who are we to identify with?

I think what almost always happens in religion is that something becomes an idol. People start out with good intentions, taking out every idolotrous thing, focusing on God alone, trying to get back to the basics of truth and love of God. But then over time whatever it was they chose to do in order to follow God better becomes an idol. I think that's what has happened with the Christian idea of God, as I alluded to some in my post on the Trinity. We have this view of God as the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, nothing more, nothing less. These are the ways we are allowed to picture God. Anything else has to fit into one of these categories or it's not "orthodox." (Even liberal Quakers are guilty of this to some degree, because by saying we can't define God and we can think of God however we want we've decided what people have to believe in order to be acceptable.)

But isn't that us deciding what God looks like? Isn't that us limiting God? Isn't that us making God fit our own image and not allowing God to knock our socks off by being something completely Other than what we could ever imagine?

It's a hard balance. I think we need common language to talk about God with, and imagery is helpful for us to grasp some piece of the relationality of this Other we're connected to. Having a common ground to speak about God is helpful because we need each other in order to understand God better. We can't just say God is whatever we want God to be. But we also need to be able to see God in new and creative ways or our faith has become dead and idolatrous.

This is something I'm passionate about, and I hope as we allow God to imagine God's self to us we can be challenged from a space of a love we can understand because it fits us personally, and because it allows our community to see the Light of God in a clearer fashion. Hopefully as we allow God to imagine God's self to us we can imagine ourselves being who God calls us to be and live that out in radical, transformative ways.

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

quaker martyr

I'm finally home and done with my midterms after being gone for the weekend.

While hanging out with friends in Northampton, MA, my husband checked his email and learned about the death of Tom Fox, the member of Christian Peacemaker Teams who had been abducted with his coworkers in November. After all this time waiting and praying perhaps I should have been ready for this news, but of course there's always that glimmer of hope--maybe they'll change. Maybe they'll see the Light and respond to it positively. Maybe a miracle will happen...

We went to Northampton Friends Meeting and many people spoke about Tom, as I'm sure happened in many meetings around the world. One Friend stood and said, "Another Quaker martyr is not something we're looking for," and added something about the fact that we're proud of his willingness to stand for what he believed.

I agree--we don't really WANT more martyrs, but it got me thinking: what is martyrdom good for? I was also thinking about this a lot last semester as I studied early church history as well as the Radical Reformation. I've been thinking about the positives and negatives of martyrdom. Tom Fox's death brought it closer to home.

So what is martyrdom for? It's obviously bad in that a person has to die, and someone has to kill them. It's also bad because sometimes people kind of want to be martyred so they'll be remembered and seen as a saint--so it's bad if there are poor intentions.

I think it can also be good in some ways, although I don't think it is ever necessary. The goal is that people would stand up for what is right, and those acting unjustly would see the error of their ways and change, allowing the would-be martyr to live. The goal is that through the life and courage of a person convicted by the Spirit to live a just and truthful life, others will see that and be challenged, and come to God themselves.

But what good is someone's death, even for a good cause, if no one changes because of it? It's good in that the person who died lived their lives fully for God, and that can never be diminshed in importance.

At the same time, I believe each martyr that is added to our ranks adds a weight of responsibility on those of us still left. Are we going to sit around mourning our loss and then get on with our lives, or are we going to take on the responsibility the martyrs have left us and live fully into our callings to truth, justice and radical love?

Another Quaker martyr is not something we want, but it is something we have. How are you--how am I--going to live out the call Tom Fox felt to work for justice in this world? Are we going to let his death remain admirable but meaningless? Or are we going to let it be a challenge and a catalyst for transformation in our individual lives and in the Society of Friends?