This week we're talking about the Trinity in systematic theology. I'm learning a lot about the theoretical concept of the "three who is one who is three...", and it's really interesting, but in some ways my Quaker practicality steps in and wonders, "Why do we spend so much time worrying about what we can never understand?"

This week we're talking about the Trinity in systematic theology. I'm learning a lot about the theoretical concept of the "three who is one who is three...", and it's really interesting, but in some ways my Quaker practicality steps in and wonders, "Why do we spend so much time worrying about what we can never understand?" Several things about the Trinity cause me not a small amount of wariness. First, it's not in the Bible, so it's really a made-up concept, one which humans hold as something that one has to believe in order to be an "orthodox" Christian. This is based on the creeds, which as a Quaker I didn't pay much attention to until this year. Now I have a much greater understanding as to why Quakers have traditionally stood against creeds! It seems like the church councils (Nicea, Constantinople, etc.) created these creeds, and now we have to decide whether we're "in" or "out," what the exact wording means, whether we can tweak the words so we can stay "in" or whether we have to leave the Christian community. I don't see this as helpful. To me it makes more sense to get to know people, learn what they believe, see if the Spirit is working in them, and by that know whether they are "Christians" or not. Words don't make us Christians, and they don't make God what we think God is.

Then there's the subordination part of the Trinitarian doctrine. My professor says you can believe that Jesus and the Spirit are subordinate to the Father without being "subordinationist," that is, making the second and third persons of the Trinity not equally God. This is tri-theism, a heresy the church rejected. The other side of this heresy is modalism, where you believe in one God who has these different faces at different times--so when he became human in Jesus he no longer existed outside of Jesus' humanity, and now that the Spirit is our access to God, the other two persons don't exist. Obviously this doesn't make sense.

And of course there's the problem of language. All three persons have been traditionally imaged as male, and although the Spirit is more of an amorphous non-gendered being in most people's minds, if pressed people would usually still refer to the Spirit as "he." If you ask people they would say God isn't male, but still, many Christians tend to think of "masculine" traits as more godly, and "feminine" traits as less valuable. This is not helpful in (at least) two ways: 1) it makes women and the attributes they are supposed to have seem less valuable while men are seen as made "more" in the image of God, and 2) it means that God cannot encompass all traits and be both what we think of as "feminine" and "masculine" in positive ways. It also makes it difficult for both genders to relate to God: how can I love a God who is male and doesn't understand what it's like to be female? How can (heterosexual) men envision being passionately in love with a God who is male?

I understand that when the doctrine of the Trinity was created, they needed to be able to express how Jesus could be God, and whether or not the Spirit was God. OK, we've established these things (at least people know that they are part of Christian doctrine). So let's get on with life! Why do we need to hold so tenaciously to this doctrine if more intelligent ways of thinking about God come to light? How do we know there are only three persons? If God is beyond our numbering system, how can we say for sure that God is one God in three and only three parts? It seems to me like these are our own stipulations, not God's.

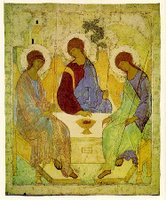

But the thing that I have learned that was most helpful was from the Cappadocians of the fourth century, and the feminist interpreter of them, Catherine M. LaCugna in "Freeing Theology." She sees their Trinitarian theology (which became the foundation of both the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches) as entirely relational. She speaks about this painting as a good way of thinking of God's relational character. It shows the three "men" of "messengers of God" that come to visit Abraham & Sarah, who provide them great hospitality. Abraham & Sarah's house is in the background, and in the middle of the table is a Eucharistic cup, symbolizing communion between the three persons. The circle is open, symbolizing the inclusivity of the Trinity's relationship: it is complete in itself but invites people in to share that communion, to return the hospitality, as Abraham and Sarah do.

But the thing that I have learned that was most helpful was from the Cappadocians of the fourth century, and the feminist interpreter of them, Catherine M. LaCugna in "Freeing Theology." She sees their Trinitarian theology (which became the foundation of both the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches) as entirely relational. She speaks about this painting as a good way of thinking of God's relational character. It shows the three "men" of "messengers of God" that come to visit Abraham & Sarah, who provide them great hospitality. Abraham & Sarah's house is in the background, and in the middle of the table is a Eucharistic cup, symbolizing communion between the three persons. The circle is open, symbolizing the inclusivity of the Trinity's relationship: it is complete in itself but invites people in to share that communion, to return the hospitality, as Abraham and Sarah do.God's essence is to be in relationship, and without someone to relate to God would cease to exist. This doesn't mean that God needs humans, but that God needs to be in some way more than one in God's self. I really like this idea--that the whole essence of the divine is love for other through and alongside and inside love for self--that they are so inextricably linked as to be the same. We are called to "love God and love our neighbor as ourself," and in God these three are the same thing although we as humans need to separate them out in our minds. This is a dynamic trio, full of movement and action, a love that is not just a passive feeling but an active being.

So to me, if it's helpful to believe in a Trinity, fine. But at the same time, we need to come up with more helpful ways to communicate these "persons" that are not only masculine metaphors, we need to remember that it's about relationship of love, and that our love requires action in the world. If the Trinity idea calls you to that, so be it. If not, it is just another dead doctrine.

Judy,

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for sharing your thoughts. It's good to know that this blogging-as-reflection, as part of my own spiritual practice, can be helpful for others' spiritual practice as well.

As regards your post, I agree--there couldn't be a time when the "ground of all being" did not exist. I think those who argue for a social trinitarian model mean that part of God's essence, of what makes God God, is a sense of being in relationship. God doesn't need us (as creation), but God's very being is relational. Obviously in one God this is difficult to imagine, hence the need for a doctrine of the Trinity.

I think this goes a long way in keeping Christians from getting stuck in the masculine-ideal-God, an autonomous figure who needs nothing and no one, and sits distant from the world, the "Unmoved Mover" who doesn't get involved in affairs of the world because "he" is immutable (unchangeable), and this interaction would change "him." So in helping us envision a God who is relational and can interact and be involved, revealing God's self to us in trees and other people and all the rest of the natural world, I see this as a powerful way of thinking about God if we don't get stuck there in the intricacies of theory.

I wish I could remember the book I read this in or article..I read something that was talking about Jesus's mother being the Holy Spirit in the Trinity...

ReplyDeleteHi, Cherice--

ReplyDeleteSo, if I keep up with your blog, can I get partial credit for the seminary courses you are taking? smile

You write: It also makes it difficult for both genders to relate to God: how can I love a God who is male and doesn't understand what it's like to be female? How can (heterosexual) men envision being passionately in love with a God who is male?

I want to point out that I often question how people of color envision and relate to God (and/or Jesus), especially in the United States. Can an African American or Asian American "love a God who is [white]...?"

We have lots of work to do.

In looking at the image of the painting you have included in this post, I thought to myself, "Given the perspective of the table, I myself am there--or nearly so--sitting with the gathered community." I feel invited, invited in.

On a different note, I also appreciate Judy's comment, especially her testimony that reading Quaker blogs is becoming a part of her spiritual practice.

At times, Quaker blogs have been questioned if we are stepping out a bit too far, since blogs are seldom under the discipline of a meeting or worship group... though I know at least two Quaker bloggers have blog elders.

I myself believe that the Quaker blogosphere is providing a form of witness and presence that is pointing to a renewal among some Friends and perhaps to an emergent Spirit among like-spirited seekers...

...but this is far off the point of your original post, so I'll stop here.

Blessings,

Liz, The Good Raised Up

lovin' life liz,

ReplyDeleteYes, that's one way people visualize the Trinity incorporating the feminine--the problem is, no one has ever said Mary was God, so that doesn't help the feminine cause a whole lot. It can be a helpful image, however, and obviously has been for Catholics throughout the centuries.

Liz Opp,

You hit the nail on the head there--I was going to mention the feeling of inclusivity of that painting, which LaCugna mentions in her article, but I forgot to write it. Great noticing! I agree and think it's so cool that God wants to include us in this relational community. Pretty powerful stuff, eh?