This may be the first in my blogged "mom fail" series, but it is definitely not the first in actual experiences of feeling like a failure as a mom. Don't worry—a lot of the time I feel like I'm doing fine. But there are just those moments when I look at myself from the outside and I think, "Who in the world is doing this crazy thing???" I assume we all have moments like that, and I always appreciate when others share their moments of failure and missed ideals (especially my friend Beth). So here you go: a mom fail around the theme of Christmas.

Yesterday, as I was patting myself on the back for doing something Advent related with my kiddos, and thinking, "Isn't this so nice? Creating memories, introducing my kids to the practice of waiting, and giving them memories that will connect them to their spiritual community and story," I encountered two experiences where I also felt like a failure as a mom.

First, my newly-minted five-year-old and I were sitting down to work on the packet of Advent stuff sent to us by our amazing pastor to children and families, Kim. Let me take a moment to tell you how awesome Kim is. This is the first year we've had Advent activities come home for the kids, but this is not the first time I have felt amazingly grateful for Kim and her ministry with my and our community's kids. She makes them look her in the eye before leaving the classroom each week, and she speaks a speaks to them individually about her gratitude for them showing up, and other personalized welcome and farewell. She journeys with them each and is aware of their strengths and weaknesses. She encourages their strengths and challenges them to grow in their spiritual lives and in their relationships with others in the classroom. She often writes special cards and notes to them so they get pieces of mail and other things addressed to them directly. OK, I didn't know this post was going to be about Kim, but there you go.

Anyway, so she sent home these Advent packets with a calendar with scratch-off circles for each day, so we did that part. Then we were coloring the nativity scene from the packet. I invited my other son, who is 8, to come join us. He didn't want to. I tried to convince him. "Advent doesn't really work if we don't do it every day, because that's kind of the point. C'mon, it will be fun! Don't you want to find out what's under today's circle?" No, he didn't. So...I forced him to come join in with the old "1...2...3..." method. Now, I can justify this because sometimes it's good to have someone hold us accountable for developing positive habits. But even as I was counting, I was cringing inside about the fact that I was forcing him to participate in a spiritual practice, as if that's going to be effective and teach "positive habits"! He did end up having fun, but of course my ideal is for him to want to participate, or for myself to be OK with offering the opportunity and letting him have the freedom of choice to do so or not.

The second "mom fail" is that as I was coloring with the 5-year-old, I asked him what he thinks Advent is about. He said, "Waiting," so I thought, "Awesome, he gets it!"

Then I asked, "What do you think we're waiting for?"

"Christmas."

"Yes, and what are we waiting for about Christmas?" I prompted.

"Presents!"

Oh dear. "Hmm...what else do you think we might be waiting for about Christmas?"

He shrugged and moved into silent-child mode.

Ack! I had, of course, fallen into the trap of asking questions with right or wrong answers, and made him feel like he had answered wrong. Eventually we got to the point where he pointed at the baby Jesus that was on one of the coloring sheets, reinforcing the idea that the Sunday school answer, "Jesus," is always the one adults are looking for. Ugh! Good thing I have a theological education.

What strikes me about this is that a) I see this as a failure as a mom, mainly because he didn't know the "right" answer, and 2) I made him feel ashamed for not giving the "right" answer. Yay for holiday traditions!

I can really see why Quakers got rid of all the holidays. What are all our holidays for anyway, and what do we communicate through them? My kids see it as the opportunity to eat lots of sugar and get more toys. Even though my 8-year-old definitely knows all the Sunday school answers about what this holiday is about, it's not really about those things for him.

In some ways I want to just get rid of all the presents and just enjoy the holiday. Thanksgiving is great (well, besides the history part), just a weekend to hang out with family and be grateful. Why does Christmas have to come with so much pressure to be able to purchase and give? This goes against everything I say I believe in about our value not being in economic terms, but I still feel incredible pressure to give Christmas gifts. I would feel ashamed if my son went to school and reported that he had not received any Christmas presents. I feel like people would judge me for not being able to afford it, or for being one of those ultra-Puritanical families who doesn't know how to celebrate and enjoy life. I feel stingy or like I'm not being generous if I don't give gifts. I enjoy receiving gifts and the special feeling of being loved and remembered that comes from someone taking the time to give me a gift, and I enjoy doing this for others. I don't want to send the message that giving gifts is somehow not spiritual or not connected to our faith tradition. So is it possible to participate in authentic giving and receiving without the focus being on materialism? Is there a way to get rid of the problematic rhythm we've created in our family system and in our culture as a whole without throwing out the whole thing?

I think early Friends went too far in getting rid of all holidays and the church calendar, because having those rhythms in life can be helpful and meaningful. But I do think we could do better at making these activities meaningful rather than falling into the traps of shame, classism, materialism, obligation, and attempting to fill ourselves up with "stuff" rather than meaning.

Friday, December 11, 2015

Monday, November 30, 2015

mini book review: the world is flat

I must admit that I only got to chapter 5 out of 17 of The World is Flat by Thomas L. Friedman. This one has been on my bookshelf for about 8 years since my husband read it for a college course, and so when I saw it as an audiobook from my library, I thought I might as well listen to it. I understood the premise already: due to globalization, there isn't the same kind of siloing of information or economic possibilities as there used to be. Since we have the Internets and easily accessible phone service, etc., many people around the world have access to similar jobs, products, services, and opportunities. What used to have to be done in-house can now be parceled out and outsourced.

While I think the premise is true, I was not interested enough in the book to continue listening to it through to the end. Maybe it got better; I probably will never know. I have two main problems with the book: first, it was kind of boring because this version (I think it's the 3rd edition) was written in 2007, and most of it is very outdated. His predictions about technology have already happened and are now old hat. It's kind of interesting reflecting on how much has changed in the last 8 years and how quickly this has become "normal," but other than that, I didn't find it interesting.

Second, Friedman seems to give this a fairly unqualified positive spin. Globalization is a good thing to him; this flattening of the economy, though scary in some ways because of the loss in the USA of certain types of jobs, is overall positive because it frees "us" up to do more interesting jobs that are higher up the ladder of creativity so we don't have to deal with menial labor, data entry, and the like.

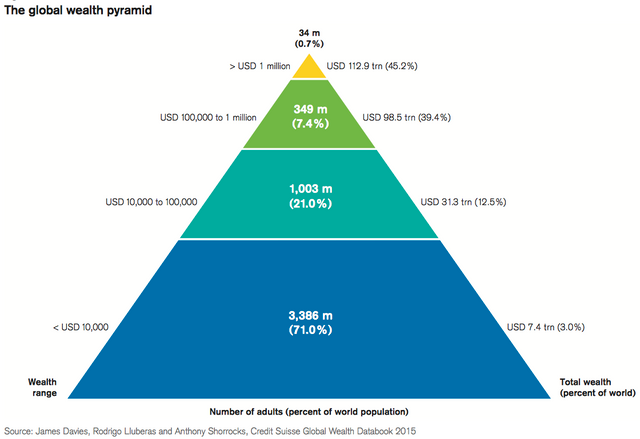

In my opinion, this doesn't seem to be true, and even if it was, it's still troubling. Basically what he's saying is not so much that the world is flat, but that the hierarchy has expanded. Now the hierarchy has a broader base from which to pull, so it feels like it's flatter to those of us in the middle classes because there are more of us in a similar range (see pyramid at right). But what the book fails to realize is the extreme pointy-ness of the world, in actuality, a fact that the Occupy movement attempted to help us recognize. There are more people competing for middle class jobs. We've sent many of them overseas, but rather than allowing Americans to have better jobs, it actually seems to mean there are often fewer jobs that provide a living wage. We are either highly skilled and can find a good paying job, or we work in the service industry or retail or some other area of the workforce that is fairly difficult work and also receives little pay.

Also, the problem with this is that it assumes a sense of superiority of Americans over people in other countries. It assumes that we deserve or are entitled to the more fun, creative jobs, and that people in other countries should be happy to take the boring jobs we don't want to do, receiving substantially less pay for it. The problem with this way of thinking is that it is still a hierarchy. In order for people around the world to move up the ladder, there has to be someone else that is so desperate for work that they will take the boring jobs after them. It's also problematic for the environment, because usually it means that the people in those places have no other alternative but to move to a city and take a job in a factory or call center because their way of life is no longer possible because their resources have been destroyed, taken over, or made toxic through pollution.

So while Friedman is correct that the Internets do make the global middle class feel flatter, I think he failed to take into account several important factors of the extreme hierarchy we are still dealing with, and the impacts this entitlement has on the world's people and land.

While I think the premise is true, I was not interested enough in the book to continue listening to it through to the end. Maybe it got better; I probably will never know. I have two main problems with the book: first, it was kind of boring because this version (I think it's the 3rd edition) was written in 2007, and most of it is very outdated. His predictions about technology have already happened and are now old hat. It's kind of interesting reflecting on how much has changed in the last 8 years and how quickly this has become "normal," but other than that, I didn't find it interesting.

Second, Friedman seems to give this a fairly unqualified positive spin. Globalization is a good thing to him; this flattening of the economy, though scary in some ways because of the loss in the USA of certain types of jobs, is overall positive because it frees "us" up to do more interesting jobs that are higher up the ladder of creativity so we don't have to deal with menial labor, data entry, and the like.

In my opinion, this doesn't seem to be true, and even if it was, it's still troubling. Basically what he's saying is not so much that the world is flat, but that the hierarchy has expanded. Now the hierarchy has a broader base from which to pull, so it feels like it's flatter to those of us in the middle classes because there are more of us in a similar range (see pyramid at right). But what the book fails to realize is the extreme pointy-ness of the world, in actuality, a fact that the Occupy movement attempted to help us recognize. There are more people competing for middle class jobs. We've sent many of them overseas, but rather than allowing Americans to have better jobs, it actually seems to mean there are often fewer jobs that provide a living wage. We are either highly skilled and can find a good paying job, or we work in the service industry or retail or some other area of the workforce that is fairly difficult work and also receives little pay.

Also, the problem with this is that it assumes a sense of superiority of Americans over people in other countries. It assumes that we deserve or are entitled to the more fun, creative jobs, and that people in other countries should be happy to take the boring jobs we don't want to do, receiving substantially less pay for it. The problem with this way of thinking is that it is still a hierarchy. In order for people around the world to move up the ladder, there has to be someone else that is so desperate for work that they will take the boring jobs after them. It's also problematic for the environment, because usually it means that the people in those places have no other alternative but to move to a city and take a job in a factory or call center because their way of life is no longer possible because their resources have been destroyed, taken over, or made toxic through pollution.

So while Friedman is correct that the Internets do make the global middle class feel flatter, I think he failed to take into account several important factors of the extreme hierarchy we are still dealing with, and the impacts this entitlement has on the world's people and land.

Monday, November 23, 2015

mini book reviews: a few by orson scott card

I've read several books by Orson Scott Card in the last few months, and I've found him to be kind of hit or miss. He's probably best known for Ender's Game, since it became a movie. A prolific author, it is fascinating to me that he can think of so many different worlds and variations on worlds.

The books I've read recently include a short novella, Space Boy, a novel called Songmaster, and the first two books in his Mither Mages Series, The Lost Gate and The Gate Thief. Of these, I would definitely recommend the Mither Mages books! The third one just came out, but it's not on audiobook at my library yet, so I unfortunately have yet to read it.

Space Boy is an interesting thought experiment that takes about three hours to listen to. What would happen if a sci-fi wormhole was actually an invisible worm that could suck someone from one world to another? What if it was in a young child's bedroom, and that's why he was afraid of monsters in his closet? Although the novella itself was not that great, the idea was intriguing.

Songmaster was somewhat better. It imagines a future where some human beings had developed the ability to sing much more powerful emotions into their music, and follows a boy named Ansett who is particularly gifted. The book explores themes of power, control, emotion, love, hate, and the maturity process. I appreciated the exploration of later life toward the end of the book, because I think many coming-of-age stories focus on the teenage and young adult years, as if that is all the coming-of-age that human beings experience, but the transitions to other life stages do not seem to be as well developed in much of literature. But I found the book overall to be lacking a solid thread of meaning and purpose.

The Mither Mages series is great! I can hardly wait to listen to the third one. This series imagines that the gods of the ancient world were actually a separate group of human-like beings, and the intermarriages we hear about in the stories of those gods ended up diluting their stock so that, though the ancient families still exist, they are not as powerful. It explains a lot of otherwise-strange phenomena in history, such as certain people who have particular connections to plants or rocks, why some people in ancient times could do miracles, and of course the reasons for all the mythology from different cultures about their gods, who apparently don't have the powers they seem to have had in the past. This series is an imaginative take on that concept. I learned quite a bit about ancient mythology, and the story was fun.

The first one takes place on Earth in a rural Virginia commune, and tells the story of a mage who is one of the first gate mages in recent history. Gates magically take people from one place to another like stepping through a gate. In the ancient world of the Mither Mages, there used to be gates all over the place, from place to place on Earth, and from Earth to other planets, but the Gate Thief stole them all. I suppose what I like most about these books, besides the imaginative ideas, is that the author shows the character moving through a variety of stages of understanding himself and his world, coming to empathize with the enemy and grapple with his own role. Is he the hero, or the villain?

The books I've read recently include a short novella, Space Boy, a novel called Songmaster, and the first two books in his Mither Mages Series, The Lost Gate and The Gate Thief. Of these, I would definitely recommend the Mither Mages books! The third one just came out, but it's not on audiobook at my library yet, so I unfortunately have yet to read it.

Space Boy is an interesting thought experiment that takes about three hours to listen to. What would happen if a sci-fi wormhole was actually an invisible worm that could suck someone from one world to another? What if it was in a young child's bedroom, and that's why he was afraid of monsters in his closet? Although the novella itself was not that great, the idea was intriguing.

Songmaster was somewhat better. It imagines a future where some human beings had developed the ability to sing much more powerful emotions into their music, and follows a boy named Ansett who is particularly gifted. The book explores themes of power, control, emotion, love, hate, and the maturity process. I appreciated the exploration of later life toward the end of the book, because I think many coming-of-age stories focus on the teenage and young adult years, as if that is all the coming-of-age that human beings experience, but the transitions to other life stages do not seem to be as well developed in much of literature. But I found the book overall to be lacking a solid thread of meaning and purpose.

The Mither Mages series is great! I can hardly wait to listen to the third one. This series imagines that the gods of the ancient world were actually a separate group of human-like beings, and the intermarriages we hear about in the stories of those gods ended up diluting their stock so that, though the ancient families still exist, they are not as powerful. It explains a lot of otherwise-strange phenomena in history, such as certain people who have particular connections to plants or rocks, why some people in ancient times could do miracles, and of course the reasons for all the mythology from different cultures about their gods, who apparently don't have the powers they seem to have had in the past. This series is an imaginative take on that concept. I learned quite a bit about ancient mythology, and the story was fun.

The first one takes place on Earth in a rural Virginia commune, and tells the story of a mage who is one of the first gate mages in recent history. Gates magically take people from one place to another like stepping through a gate. In the ancient world of the Mither Mages, there used to be gates all over the place, from place to place on Earth, and from Earth to other planets, but the Gate Thief stole them all. I suppose what I like most about these books, besides the imaginative ideas, is that the author shows the character moving through a variety of stages of understanding himself and his world, coming to empathize with the enemy and grapple with his own role. Is he the hero, or the villain?

Wednesday, November 04, 2015

mini book review: augustine for armchair theologians

I listened to the audiobook of Augustine for Armchair Theologians (Stephen A. Cooper, 2002) mainly out of curiosity for what the author would say to "armchair theologians," although as someone who has a master of divinity degree and teaches in a seminary, I probably don't exactly count as an armchair theologian. What I appreciated about this book is that it went through the entire book of his Confessions and pulled out important moments and key points, and placed them within their cultural milieu in a way that likely would make sense for the average college-educated reader. This is a very accessible text and gives a good overview of Augustine's life and struggles, and the reasons behind those struggles, which may not be entirely clear if one was reading through the Confessions unaided. It also includes a brief overview of City of God.

I realized that previously, though I read the Confessions and City of God years ago, I was mainly reading them for his theology, and to learn about church history in his lifetime, and not so much for learning about his life and personal experience. Yes, I assign chapters from his Confessions when I teach church history to undergrads, so I was very aware of his conversion experiences and other highlights, but I hadn't spent a lot of time learning more than the basics of his biography. I enjoyed hearing Coopers explanation of why Augustine thought and emphasized certain things, and I appreciated his emphasis on the strangeness of Augustine's coming to God through "pagan" books.

I didn't like some of the presumptions Cooper made about Augustine's correctness or incorrectness of theological insight. In many places in the book he presented information and left it up for the reader to decide what was right and true, but especially toward the end of the text, after Augustine's conversion, Cooper makes more values-based statements about the correctness of Augustine's theology. It would have been better had he said something like, "This disagrees with the later version of orthodoxy according to [some council or pope]," but instead he made blanket statements about whether it was right or wrong without a lot of context for what branch of Christianity his judgments flow from.

In the past, I admit, when I've read Augustine it has often been to disagree with him, since much of the Just War Theory is based on his writings. I enjoyed the chance to get to know the man behind the theology. It gives me a better basis for empathy for his belief system.

I recommend this book to those interested in learning more about Augustine, but if you haven't read the Confessions or City of God yourself, I encourage you to read those afterwards, too.

I realized that previously, though I read the Confessions and City of God years ago, I was mainly reading them for his theology, and to learn about church history in his lifetime, and not so much for learning about his life and personal experience. Yes, I assign chapters from his Confessions when I teach church history to undergrads, so I was very aware of his conversion experiences and other highlights, but I hadn't spent a lot of time learning more than the basics of his biography. I enjoyed hearing Coopers explanation of why Augustine thought and emphasized certain things, and I appreciated his emphasis on the strangeness of Augustine's coming to God through "pagan" books.

I didn't like some of the presumptions Cooper made about Augustine's correctness or incorrectness of theological insight. In many places in the book he presented information and left it up for the reader to decide what was right and true, but especially toward the end of the text, after Augustine's conversion, Cooper makes more values-based statements about the correctness of Augustine's theology. It would have been better had he said something like, "This disagrees with the later version of orthodoxy according to [some council or pope]," but instead he made blanket statements about whether it was right or wrong without a lot of context for what branch of Christianity his judgments flow from.

In the past, I admit, when I've read Augustine it has often been to disagree with him, since much of the Just War Theory is based on his writings. I enjoyed the chance to get to know the man behind the theology. It gives me a better basis for empathy for his belief system.

I recommend this book to those interested in learning more about Augustine, but if you haven't read the Confessions or City of God yourself, I encourage you to read those afterwards, too.

Tuesday, November 03, 2015

mini book review: blue like jazz: nonreligious thoughts on christian spirituality

I finally got around to reading (or at least listening to) Blue Like Jazz: Nonreligious thoughts on Christian spirituality (2003), a book that was fairly popular in my social circles over the last several years since the author, Donald Miller, is from Portland, OR and is an Evangelical Christian who writes about social activism. I hadn't read the book before, partially because it was so popular and trendy, so I thought it was ironic that he makes fun of Trendy Author (or, really, himself because he was judging Trendy Author), a Northwest author who writes about fishing and gave a reading at Powell's (one can surmise it's David James Duncan, except that he said the author is an Oregonian, and Duncan is a Montanan). At any rate, I think I kind of wrote off Blue Like Jazz in a similar way to the criticism Miller has of Trendy Author: that from what I heard, he was spouting a version of Christianity with just the right amount of edginess to get Evangelical Christians to think they're getting out of their comfort zones into something exciting.

Well, the book was not terrible. There were things I liked about it. I had already heard the confession booth story, where he and his friends set up a reverse confession booth at Reed College, and I would probably assign that for students to read. It was pretty powerful. That was probably my favorite chapter. There was also a pretty good chapter about tithing, although leaving one with the impression that if you just start tithing, money will start flowing to you. Maybe, but that leaves the problem of those for whom that doesn't happen. The last several chapters were the most interesting, and although I wasn't as interested in the early chapters, I'm not sure if the last several would have made sense without following him through the whole story. At the same time, his story is not told linearly, so it may not matter. The end of the book is more thematic rather than story-driven, so probably others might like the other chapters more and I'm just weird!

I was a little confused about who his audience is meant to be. I think probably he's aiming at those who are Evangelical Christians, or who were raised so, but who are frustrated with the church. I think he's trying to show that there's another way to be an Evangelical Christian than the close-minded, judgmental, fundamentalist, biblical literalists that he grew up with. He may be thinking that he's going to reach people who aren't Christians, but I think the Christianese would probably not be accessible for many people who didn't grow up in the church.

I would tentatively recommend this book to people who want to be Christians and come from an Evangelical or Fundamentalist background, but who are disenchanted with the church, and who aren't comfortable with a completely radical reorientation of their faith but who just need a bit healthier of a spin on things. I would not recommend this book to people who are already thinking deeply about their faith (or even their not-faith), or to most Friends. I found the book a little bit sexist, although I appreciate that he recognizes that he's not that great at relationships with women, so I think he just didn't really know how to approach the topic well. I also didn't like that he seemed to be bringing up some things just to shock people and make them think they were reading something edgy. Those sections came across as just for show and to sell books.

I do think Miller is genuine, though, and that he wants to sell books because he wants people to realize that God isn't a slot machine or a punitive judge, and that people are really changed through encountering Jesus in community. Miller shares some fairly personal experiences of failure or of missing the mark, and I appreciated his humility and willingness to learn from these experiences.

Well, the book was not terrible. There were things I liked about it. I had already heard the confession booth story, where he and his friends set up a reverse confession booth at Reed College, and I would probably assign that for students to read. It was pretty powerful. That was probably my favorite chapter. There was also a pretty good chapter about tithing, although leaving one with the impression that if you just start tithing, money will start flowing to you. Maybe, but that leaves the problem of those for whom that doesn't happen. The last several chapters were the most interesting, and although I wasn't as interested in the early chapters, I'm not sure if the last several would have made sense without following him through the whole story. At the same time, his story is not told linearly, so it may not matter. The end of the book is more thematic rather than story-driven, so probably others might like the other chapters more and I'm just weird!

I was a little confused about who his audience is meant to be. I think probably he's aiming at those who are Evangelical Christians, or who were raised so, but who are frustrated with the church. I think he's trying to show that there's another way to be an Evangelical Christian than the close-minded, judgmental, fundamentalist, biblical literalists that he grew up with. He may be thinking that he's going to reach people who aren't Christians, but I think the Christianese would probably not be accessible for many people who didn't grow up in the church.

I would tentatively recommend this book to people who want to be Christians and come from an Evangelical or Fundamentalist background, but who are disenchanted with the church, and who aren't comfortable with a completely radical reorientation of their faith but who just need a bit healthier of a spin on things. I would not recommend this book to people who are already thinking deeply about their faith (or even their not-faith), or to most Friends. I found the book a little bit sexist, although I appreciate that he recognizes that he's not that great at relationships with women, so I think he just didn't really know how to approach the topic well. I also didn't like that he seemed to be bringing up some things just to shock people and make them think they were reading something edgy. Those sections came across as just for show and to sell books.

I do think Miller is genuine, though, and that he wants to sell books because he wants people to realize that God isn't a slot machine or a punitive judge, and that people are really changed through encountering Jesus in community. Miller shares some fairly personal experiences of failure or of missing the mark, and I appreciated his humility and willingness to learn from these experiences.

Friday, October 30, 2015

mini book review: black elk speaks

I listened to the audiobook, Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux (ed. by John G. Neihardt), for the last couple of days. This is a really powerful text, a transcript of Black Elk's story as he told it to Neihardt around 1930. Apparently, Neihardt went to listen to Black Elk, who said he wanted to tell him his story, and wanted Neihardt to write it down and share it. Black Elk lived from 1863-1950, so he witnessed pretty much the whole scope of transition from his Lakota people's traditional way of life to their consignment to reservations.

The story is a sad one, of course, since we all know the trajectory forced on his people in that century. Some of the sadness for me personally comes from white guilt, I suppose — what were my ancestors thinking?! What were the Quakers doing and why weren't they helping? Oh yeah, some of them were working on abolition and women's rights. And some of them were thinking about moving west and establishing a Quaker community out in Oregon Territory. About the time of Black Elk's first vision, William Hobson visited the Chehalem Valley and decided it was a perfect place for his "garden of the Lord." In other words, Quakers were expanding into lands accessible because of the native people being forced onto reservations.

Some of my sadness comes from the loss of knowledge of the land, how to live on it, and how to connect with God here in this place. I don't hear anything in Black Elk's visions that seems different from how I can imagine the God of the Bible speaking. Many people in the Bible have visions, with symbols, animals, weather phenomena, knowledge of the future, and intuitive understanding being received or experienced through their visions for the community. We have these recorded throughout the Bible, especially by Ezekiel, Daniel, and John. Our own Quaker John, John Woolman, went to spend time with Native Americans and realized they already knew the same God. I want to use this as a badge of honor, that my people were not completely to blame for what happened to the Native Americans, but I think sometimes I use the highlights of Quaker heritage as a defensive shield so I don't have to feel all the weight of a history of oppression and violence.

My intense sadness comes from loss of the kind of connection to God in this place that Black Elk knew. I mean, he wasn't here in the Pacific Northwest, but he knew his own land in that way, and his spirituality was tied intensely to his place. Probably there were people here on my land who knew this place and how to recognize when God speaks here. This is not to say that Black Elk didn't understand a universal God, because it sounds like he did. It sounds like he knew a universal Creator God who spoke to him through his particular place: the creatures and the land that formed his world. God spoke to him in visions, but they were for the people. They weren't for some far off land of heaven or for personal edification, or mystical oneness for the ecstatic feeling of the mystic. They were for the people's happiness, the people's right relationship with God and the land.

I don't want to overly romanticize this time, because it sounds like it wasn't exactly egalitarian for women, and I'm sure life wasn't easy for his people. Looking back on his childhood after 60 years, he probably remembered it with a bit of nostalgia, and mainly thought of the good times, comparing an idyllic childhood with the complete brokenness his people experienced during the course of his adult years. But the visions he shares and the way he shares them speak from the same wellspring of Truth that I recognize in other spiritual writers. He knew God. God spoke to him in unusual ways, even for his people, but his people had a context and a language for that way of knowing. It was a mystical way of knowing, but it was intimately connected and tied to the physical reality of the land, the very herbs, the health of individuals and the community.

As Quakers, I so appreciate our mystical bent, our ability to listen well and to try to discern together what God is saying. But we are a very disembodied religion. We don't have anything tying us to a certain place, and sometimes we are criticized for being too intellectual. I think this criticism is probably pretty accurate. We are too much in our heads and we don't know (as a community, though I'm sure there are individuals who do) how to connect this to our place. What would it look like to be Friends of our watershed, Friends of our land, in ways that were wholly and specifically idiosyncratic to our bioregion and our even more particular places?

The story is a sad one, of course, since we all know the trajectory forced on his people in that century. Some of the sadness for me personally comes from white guilt, I suppose — what were my ancestors thinking?! What were the Quakers doing and why weren't they helping? Oh yeah, some of them were working on abolition and women's rights. And some of them were thinking about moving west and establishing a Quaker community out in Oregon Territory. About the time of Black Elk's first vision, William Hobson visited the Chehalem Valley and decided it was a perfect place for his "garden of the Lord." In other words, Quakers were expanding into lands accessible because of the native people being forced onto reservations.

Some of my sadness comes from the loss of knowledge of the land, how to live on it, and how to connect with God here in this place. I don't hear anything in Black Elk's visions that seems different from how I can imagine the God of the Bible speaking. Many people in the Bible have visions, with symbols, animals, weather phenomena, knowledge of the future, and intuitive understanding being received or experienced through their visions for the community. We have these recorded throughout the Bible, especially by Ezekiel, Daniel, and John. Our own Quaker John, John Woolman, went to spend time with Native Americans and realized they already knew the same God. I want to use this as a badge of honor, that my people were not completely to blame for what happened to the Native Americans, but I think sometimes I use the highlights of Quaker heritage as a defensive shield so I don't have to feel all the weight of a history of oppression and violence.

My intense sadness comes from loss of the kind of connection to God in this place that Black Elk knew. I mean, he wasn't here in the Pacific Northwest, but he knew his own land in that way, and his spirituality was tied intensely to his place. Probably there were people here on my land who knew this place and how to recognize when God speaks here. This is not to say that Black Elk didn't understand a universal God, because it sounds like he did. It sounds like he knew a universal Creator God who spoke to him through his particular place: the creatures and the land that formed his world. God spoke to him in visions, but they were for the people. They weren't for some far off land of heaven or for personal edification, or mystical oneness for the ecstatic feeling of the mystic. They were for the people's happiness, the people's right relationship with God and the land.

I don't want to overly romanticize this time, because it sounds like it wasn't exactly egalitarian for women, and I'm sure life wasn't easy for his people. Looking back on his childhood after 60 years, he probably remembered it with a bit of nostalgia, and mainly thought of the good times, comparing an idyllic childhood with the complete brokenness his people experienced during the course of his adult years. But the visions he shares and the way he shares them speak from the same wellspring of Truth that I recognize in other spiritual writers. He knew God. God spoke to him in unusual ways, even for his people, but his people had a context and a language for that way of knowing. It was a mystical way of knowing, but it was intimately connected and tied to the physical reality of the land, the very herbs, the health of individuals and the community.

As Quakers, I so appreciate our mystical bent, our ability to listen well and to try to discern together what God is saying. But we are a very disembodied religion. We don't have anything tying us to a certain place, and sometimes we are criticized for being too intellectual. I think this criticism is probably pretty accurate. We are too much in our heads and we don't know (as a community, though I'm sure there are individuals who do) how to connect this to our place. What would it look like to be Friends of our watershed, Friends of our land, in ways that were wholly and specifically idiosyncratic to our bioregion and our even more particular places?

Thursday, October 29, 2015

mini book review: the sense of wonder

By Rachel L. Carson, author of Silent Spring, this little book, The Sense of Wonder (1965), takes only a little over half an hour to listen to as an audiobook. It's a beautiful little piece that encourages us to inculcate a sense of wonder in our children. She talks about how this is more important than knowledge, because we can learn more information as we get older, but developing a sense of wonder if we haven't developed it as a child is much more difficult. She talks about how each of us can take children outside, or even sit and look out a window, watching the birds or small creatures we see, stooping to pick up a small leaf or shell to examine carefully. We can take kids outside at night to look at the wonder of the stars and moon, or we can walk on the beach and notice and experience awe.

What I liked most about this book is that she really attempts to make these suggestions accessible. One doesn't have to be a scientist or a naturalist in order to spend time exploring and experiencing wonder with kids. She made it clear that an adult need not know the names for everything — or for anything! But just noticing and being present to the experience is what's important. Carson talks about spending time with her small nephew, and how she would take him out on the beach at night to experience a storm, or walk through the woods in different seasons. When it was too cold or wet to go out, they looked out her window, but she also recognized that for children, it's fun and exciting to go outside on a wet day and experience the world that comes out in the rain. She talked about noticing birds, even if one can't identify them, paying attention to when they appear and wondering about migratory patterns. For those with the privilege of a microscope or a telescope, more in-depth explorations can happen, such as looking at the moon with a telescope and waiting for migrating birds to pass between us and the moon.

I loved this playful and insightful book, and I hope to put some of her ideas into practice with my kids. Her insight about the greater importance of wonder over knowledge was something I have known but had never put into words, and it provides a new freedom for me, since I don't know the names of all the birds or information about all the plants. But my sons and I do have fun collecting bugs or watching birds, noticing seasonal changes, listening to the sounds we can hear from our yard, and attending to tiny patterns and vast cloud formations. This gives me a renewed sense of excitement to do this more often.

What I liked most about this book is that she really attempts to make these suggestions accessible. One doesn't have to be a scientist or a naturalist in order to spend time exploring and experiencing wonder with kids. She made it clear that an adult need not know the names for everything — or for anything! But just noticing and being present to the experience is what's important. Carson talks about spending time with her small nephew, and how she would take him out on the beach at night to experience a storm, or walk through the woods in different seasons. When it was too cold or wet to go out, they looked out her window, but she also recognized that for children, it's fun and exciting to go outside on a wet day and experience the world that comes out in the rain. She talked about noticing birds, even if one can't identify them, paying attention to when they appear and wondering about migratory patterns. For those with the privilege of a microscope or a telescope, more in-depth explorations can happen, such as looking at the moon with a telescope and waiting for migrating birds to pass between us and the moon.

I loved this playful and insightful book, and I hope to put some of her ideas into practice with my kids. Her insight about the greater importance of wonder over knowledge was something I have known but had never put into words, and it provides a new freedom for me, since I don't know the names of all the birds or information about all the plants. But my sons and I do have fun collecting bugs or watching birds, noticing seasonal changes, listening to the sounds we can hear from our yard, and attending to tiny patterns and vast cloud formations. This gives me a renewed sense of excitement to do this more often.

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

mini book review: the religion of small societies

I recently listened to The Religion of Small Societies, by Ninian Smart, part of the Audio Classics Series on Religion, Scriptures & Spirituality (and narrated by Ben Kingsley, no less than Gandhi himself, right?). I think it's made for audio (as opposed to other books that are written for reading and only later are made into audiobooks). It was interesting and fairly well done.

I was most interested in the parts that had to do with numinous experiences that people had, where they encountered God/dess or a god/dess. These were really interesting and beautiful to hear about. The author talked about the difference between spirituality and other parts of life in that numinous experience, that experience of the direct presence of the holy. Shamans may have been the ones who most frequently had these numinous experiences, but it sounds like they sometimes happened to ordinary members of the tribe or group, too.

One reason that I wanted to listen to this book was that I have this growing sense that it's the vastness of our society that is one of the reasons we're seeing so many problems in our world. In a small society, there is accountability. Everyone pretty much knows what everyone is up to. There is no hiding in anonymity, and not as much ability to get lost in the shuffle and grow so lonely and depressed that you lash out through a school shooting, for example, or trafficking young children, or where you can take and take more resources than you need in a futile attempt to keep yourself from feeling vulnerable and alone. But in our society, there is no accountability like that, there is no way to make sure that everyone is doing OK, there is no effective mechanism that reminds us that others are hungry and that we must share.

Small societies often have religions that are place-based, that see God/dess in a particular place or that see the divine in the other animate and inanimate entities that make up their world. While perhaps this kind of animism is "primitive," a precursor to a more universal understanding of the divine, a God/dess who is present in all places and not bound to a particular plant, animal, or rock, sometimes I feel like our transcendent understanding of God gets in the way of our ability to connect with God on an immanent plane. When we as Christians became place-less and universal, we became so susceptible to the eventual wedding with empire that occurred with Rome, to the monoculture of convert or die, which wiped out so many of these small religions in the last 2000 years. A victory for Jesus, or just a victory for empire? It's so hard to tell sometimes.

Now as a people we're realizing that our disconnection from the land is harming not only ourselves, but also all the other creatures and non-living entities on the land. (Or at least, it's harming their ability to survive in the way that we have for thousands of years. We will all have to adapt.) Some of us are realizing that what these small societies did, creating accountability with one another, setting up guidelines for how to live in a way that did not overly-deplete the resources of our beloved place, were actually really smart. Perhaps as Americans we grew up learning that Native Americans didn't manage the land, so Europeans had to come in and do so for them, but now we're learning that Native peoples were managing the land, just in such a sustainable way that it looked natural. The size of their groups and the particular rules in place in their communities almost all contributed to maintaining the land for the benefit of all — not just the people but the entire ecosystem.

We obviously can't go back to that kind of society, but I've wondered for a long time what it would look like to live in this kind of tribal way, at least to form our meetings/congregations in such a way that we split in healthy ways when we get too big, and where we actually know one another and supply one another's needs. What if we not only did this for the people, but for the whole ecosystems to which we're connected? Some people are calling this watershed discipleship or place-based theology. What if we paid attention to the numinous experiences we had here, in this place, of the God/dess who is particular to here, and transcends space and time? What might we learn if we paid attention to being followers of Jesus here, rather than in some disembodied future?

I was most interested in the parts that had to do with numinous experiences that people had, where they encountered God/dess or a god/dess. These were really interesting and beautiful to hear about. The author talked about the difference between spirituality and other parts of life in that numinous experience, that experience of the direct presence of the holy. Shamans may have been the ones who most frequently had these numinous experiences, but it sounds like they sometimes happened to ordinary members of the tribe or group, too.

One reason that I wanted to listen to this book was that I have this growing sense that it's the vastness of our society that is one of the reasons we're seeing so many problems in our world. In a small society, there is accountability. Everyone pretty much knows what everyone is up to. There is no hiding in anonymity, and not as much ability to get lost in the shuffle and grow so lonely and depressed that you lash out through a school shooting, for example, or trafficking young children, or where you can take and take more resources than you need in a futile attempt to keep yourself from feeling vulnerable and alone. But in our society, there is no accountability like that, there is no way to make sure that everyone is doing OK, there is no effective mechanism that reminds us that others are hungry and that we must share.

Small societies often have religions that are place-based, that see God/dess in a particular place or that see the divine in the other animate and inanimate entities that make up their world. While perhaps this kind of animism is "primitive," a precursor to a more universal understanding of the divine, a God/dess who is present in all places and not bound to a particular plant, animal, or rock, sometimes I feel like our transcendent understanding of God gets in the way of our ability to connect with God on an immanent plane. When we as Christians became place-less and universal, we became so susceptible to the eventual wedding with empire that occurred with Rome, to the monoculture of convert or die, which wiped out so many of these small religions in the last 2000 years. A victory for Jesus, or just a victory for empire? It's so hard to tell sometimes.

Now as a people we're realizing that our disconnection from the land is harming not only ourselves, but also all the other creatures and non-living entities on the land. (Or at least, it's harming their ability to survive in the way that we have for thousands of years. We will all have to adapt.) Some of us are realizing that what these small societies did, creating accountability with one another, setting up guidelines for how to live in a way that did not overly-deplete the resources of our beloved place, were actually really smart. Perhaps as Americans we grew up learning that Native Americans didn't manage the land, so Europeans had to come in and do so for them, but now we're learning that Native peoples were managing the land, just in such a sustainable way that it looked natural. The size of their groups and the particular rules in place in their communities almost all contributed to maintaining the land for the benefit of all — not just the people but the entire ecosystem.

We obviously can't go back to that kind of society, but I've wondered for a long time what it would look like to live in this kind of tribal way, at least to form our meetings/congregations in such a way that we split in healthy ways when we get too big, and where we actually know one another and supply one another's needs. What if we not only did this for the people, but for the whole ecosystems to which we're connected? Some people are calling this watershed discipleship or place-based theology. What if we paid attention to the numinous experiences we had here, in this place, of the God/dess who is particular to here, and transcends space and time? What might we learn if we paid attention to being followers of Jesus here, rather than in some disembodied future?

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

mini book review: the game of thrones

Lest you think I only read high-brow literature and popular nonfiction in my spare time, I did also spend a good portion of my summer listening to the audiobooks of A Game of Thrones series by George R. R. Martin (technically, the series is called "The Song of Ice and Fire"). I started into this series by watching a couple episodes of the TV series, but those were too racy for me. The books are not as graphic. They were addicting, however! I found myself making up excuses to do dishes or laundry so I could listen to my audiobook. Luckily, a bunch of people at my library are also interested in this series, so I had to wait on a waitlist for weeks between each book, so I couldn't just binge my way through them (though I suppose it would have had a positive effect on my housework). The book is set in a different world where each season lasts many of our years. It's a medieval society with knights and horses and dragons, battles, love, intrigue, jealousy, a bit of magic and religion, and much familial drama.

I'm not sure what it is about this series that is likable. Just because a character is likable doesn't mean they'll survive (if you know anything about Game of Thrones I'm sure this isn't news to you — I heard about the end of the first book on NPR one day!). Usually I like sci-fi and fantasy because it lets the author and reader explore moral and ethical questions that aren't really possible to explore in normal life. But I can't say that these books have any shining moral truths to present, except, perhaps, that we don't always get what we deserve. It's an intriguing look at the "game of thrones," as in, the intrigue one has to participate in if one happens to be born into a noble family, or wants to participate in the life of lords and ladies. This is not a situation most of us find ourselves in nowadays, but I suppose the politics and attempts to get ahead are just as real, though far less bloody, at least here in the US.

I was excited to read the fifth book because I thought that would be the end of the series and there would be some kind of closure, but by the time I got half way through the book and realized none of these story lines were drawing to a close, and in fact new storylines were opening all the time, I looked it up and realized that the author is still working on the next book. Agh! I think book companies should do what Netflix and other video streaming places have been doing lately, and release a whole series at once so we can binge on it all at one time. None of this delayed gratification thing!

Seriously, though, I probably will keep reading it, as it's a good story. It definitely keeps my interest and entertains. The characters are unique. They're not exactly realistic or well-rounded, they're kind of like mythical foils without a lot of character depth, but they're interesting and you never quite know what they're going to do.

I'm not sure what it is about this series that is likable. Just because a character is likable doesn't mean they'll survive (if you know anything about Game of Thrones I'm sure this isn't news to you — I heard about the end of the first book on NPR one day!). Usually I like sci-fi and fantasy because it lets the author and reader explore moral and ethical questions that aren't really possible to explore in normal life. But I can't say that these books have any shining moral truths to present, except, perhaps, that we don't always get what we deserve. It's an intriguing look at the "game of thrones," as in, the intrigue one has to participate in if one happens to be born into a noble family, or wants to participate in the life of lords and ladies. This is not a situation most of us find ourselves in nowadays, but I suppose the politics and attempts to get ahead are just as real, though far less bloody, at least here in the US.

I was excited to read the fifth book because I thought that would be the end of the series and there would be some kind of closure, but by the time I got half way through the book and realized none of these story lines were drawing to a close, and in fact new storylines were opening all the time, I looked it up and realized that the author is still working on the next book. Agh! I think book companies should do what Netflix and other video streaming places have been doing lately, and release a whole series at once so we can binge on it all at one time. None of this delayed gratification thing!

Seriously, though, I probably will keep reading it, as it's a good story. It definitely keeps my interest and entertains. The characters are unique. They're not exactly realistic or well-rounded, they're kind of like mythical foils without a lot of character depth, but they're interesting and you never quite know what they're going to do.

Monday, October 26, 2015

mini book review: in defense of food

I recently (finally) listened to In Defense of Food by Michael Pollan on audiobook. He tells us his main point right up front: "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants." Then he spends the rest of the book unpacking what this means: "eating," as in, not gorging, and eating as a social occasion rather than something we do by ourselves in front of the TV or just for the sake of ingesting nutrients. "Food," as in, actual food rather than some processed pseudo-food, and cooking it ourselves so we know what goes into it and so we're participants in the process and therefore value each bite more than we otherwise would. "Not too much," of course, refers to the American propensity to eat huge portions with high calories. "Plants" doesn't require much definition, except that with statistics like the fact that it takes 3-4 of today's apples to equal the nutritional value of one 1950s apple due to soil nutrient depletion as well as human selection for visual appeal and high yield, we have selected against nutrient content in many of our staple foods. He also suggests in the final pages that we participate in the food production process, if only by way of a small herb garden on a window sill, or more if we have space.

Another main point in this book is about "nutritionism." Pollan talks about the science of nutrition as almost a religion, and the irony that Americans are so fanatical about "health" and are one of the most unhealthy populations in the "developed" world.

He also gives a lot of information regarding "the Western diet," by which he means the processed food (or what passes for food) that many Americans eat. He says, interestingly, that pretty much any traditional diet produces fairly healthy people with low risk for "Western diseases" such as cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. People who eat any traditional diet are, on the whole, much healthier than the population eating a Western diet. Pollan cited a fascinating study of Australian aborigines who had adopted a Western diet and had developed diabetes. A researcher had them go out into the bush and hunt and gather for their sustenance again. The study lasted for 7 weeks, during which time they lost an average of 17 pounds and their diabetes was much more controlled.

Pollan connects the dots that a Western diet, although supposedly superior because it's based on science, is actually making us sicker. He gives a number of helpful and practical suggestions about how to eat more healthily, not just by falling into the trap of a shiny new diet to try (a nutritionist perspective), but by shifting our perspective from food as a means to the end of survival, to real food as an enjoyable experience in which we participate as a community.

Since this is a mini-review, I'll leave it there, saying I agree with Pollan's conclusions, and this is basically how I've been eating for several years now. But there are some criticisms of Pollan's approach, not surprisingly, from the field of nutrition and science. Since Pollan's point is basically that science's approach to food is to reductionist, these critiques are not surprising, but it is difficult for those of us having been brought up in a culture that relies so heavily on scientific evidence to just stop listening to science. I don't think Pollan would have us do that, but to pay attention to the ways that science is being used and the assumptions upon which it is based, striving for scientific processes that actually serve us rather than leading us down the path toward tinier and tinier meaningless reductionist minutiae.

Another main point in this book is about "nutritionism." Pollan talks about the science of nutrition as almost a religion, and the irony that Americans are so fanatical about "health" and are one of the most unhealthy populations in the "developed" world.

He also gives a lot of information regarding "the Western diet," by which he means the processed food (or what passes for food) that many Americans eat. He says, interestingly, that pretty much any traditional diet produces fairly healthy people with low risk for "Western diseases" such as cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. People who eat any traditional diet are, on the whole, much healthier than the population eating a Western diet. Pollan cited a fascinating study of Australian aborigines who had adopted a Western diet and had developed diabetes. A researcher had them go out into the bush and hunt and gather for their sustenance again. The study lasted for 7 weeks, during which time they lost an average of 17 pounds and their diabetes was much more controlled.

Pollan connects the dots that a Western diet, although supposedly superior because it's based on science, is actually making us sicker. He gives a number of helpful and practical suggestions about how to eat more healthily, not just by falling into the trap of a shiny new diet to try (a nutritionist perspective), but by shifting our perspective from food as a means to the end of survival, to real food as an enjoyable experience in which we participate as a community.

Since this is a mini-review, I'll leave it there, saying I agree with Pollan's conclusions, and this is basically how I've been eating for several years now. But there are some criticisms of Pollan's approach, not surprisingly, from the field of nutrition and science. Since Pollan's point is basically that science's approach to food is to reductionist, these critiques are not surprising, but it is difficult for those of us having been brought up in a culture that relies so heavily on scientific evidence to just stop listening to science. I don't think Pollan would have us do that, but to pay attention to the ways that science is being used and the assumptions upon which it is based, striving for scientific processes that actually serve us rather than leading us down the path toward tinier and tinier meaningless reductionist minutiae.

Monday, May 11, 2015

why I was late to worship yesterday, a.k.a. reasons I love North Valley

Yesterday, my family and I arrived at the meetinghouse right on time for worship, and my husband ran in to help lead music. I, however, did not arrive until at least five minutes in, and it hit me as I took my seat how grateful I am to be part of the community at North Valley Friends because of all the reasons that made me late.

First, I was getting something out of the trunk when a Friend drove up and stopped to chat. She offered to loan us a 3/4 size guitar for my boys to learn on, a loaner we can keep as long as we like. Just that morning, my 8-year-old had been saying he wants to be able to do something to help in worship, and asking to take his full-size guitar to worship practice with his dad. He's been working hard to learn chords, but it's pretty challenging on a full-size guitar with hands his size, so this was a perfect and timely gift.

I pulled a bag of clothes out of the trunk to take to the ReThreads shed, a drop-off site for used clothes. ReThreads is open to North Valley folk as well as the rest of the community. A group of people from North Valley sort all the donations left in their storage shed, put them on hangers, and take them to a two-room "store" next to our meetinghouse. Last summer, they spent time fixing up the "store," painting it inside and out, adding decorations, and making the place inviting. My sons had long since run in to the meetinghouse for worship.

Before I could make it to the ReThreads drop-off, I saw someone in the parking lot to whom I was going to give a flat of onions. This summer, our community garden has expanded to not just the garden space on the meetinghouse property, but also to a coordinated effort with all the gardens of North Vally people who want to be involved. Each person is in charge of a particular crop, and we'll bring our produce to share with one another throughout the summer. Since I don't have room in my yard to grow a bunch of different crops, this is so exciting! I'm waiting in anticipation of what delightful produce will be shared, and I'm excited to share my own small offering.

To get to the flat of onions I had to move aside a bike rack we're loaning to some Friends for the week. We have an e-group at North Valley, and probably at least once a week there are emails requesting to borrow things and offering to give things away or sell them, in addition to emails about births, deaths, weddings, community news, and notifications about North Valley events. We've benefited from this e-group many times, and it's great when we can also help supply someone else's need.

I finally got to drop off my used clothes at ReThreads and went inside, where I found one son munching baked goods in the foyer. We get day-olds sometimes from a local bakery, and I picked up a loaf of bread to take home to nourish our family for the week. Meanwhile, I chatted with two wonderful ladies whose lives intersect with mine not often, but deeply.

By this point I had thoroughly lost my children. I went into the meeting space and looked around, confusedly, before a Friend pointed toward the children's wing. I went to check on them, and they were already in their "places of worship," engrossed in that work and at home in their place.

I returned to the adult meeting space and joined the song.

First, I was getting something out of the trunk when a Friend drove up and stopped to chat. She offered to loan us a 3/4 size guitar for my boys to learn on, a loaner we can keep as long as we like. Just that morning, my 8-year-old had been saying he wants to be able to do something to help in worship, and asking to take his full-size guitar to worship practice with his dad. He's been working hard to learn chords, but it's pretty challenging on a full-size guitar with hands his size, so this was a perfect and timely gift.

I pulled a bag of clothes out of the trunk to take to the ReThreads shed, a drop-off site for used clothes. ReThreads is open to North Valley folk as well as the rest of the community. A group of people from North Valley sort all the donations left in their storage shed, put them on hangers, and take them to a two-room "store" next to our meetinghouse. Last summer, they spent time fixing up the "store," painting it inside and out, adding decorations, and making the place inviting. My sons had long since run in to the meetinghouse for worship.

Before I could make it to the ReThreads drop-off, I saw someone in the parking lot to whom I was going to give a flat of onions. This summer, our community garden has expanded to not just the garden space on the meetinghouse property, but also to a coordinated effort with all the gardens of North Vally people who want to be involved. Each person is in charge of a particular crop, and we'll bring our produce to share with one another throughout the summer. Since I don't have room in my yard to grow a bunch of different crops, this is so exciting! I'm waiting in anticipation of what delightful produce will be shared, and I'm excited to share my own small offering.

To get to the flat of onions I had to move aside a bike rack we're loaning to some Friends for the week. We have an e-group at North Valley, and probably at least once a week there are emails requesting to borrow things and offering to give things away or sell them, in addition to emails about births, deaths, weddings, community news, and notifications about North Valley events. We've benefited from this e-group many times, and it's great when we can also help supply someone else's need.

I finally got to drop off my used clothes at ReThreads and went inside, where I found one son munching baked goods in the foyer. We get day-olds sometimes from a local bakery, and I picked up a loaf of bread to take home to nourish our family for the week. Meanwhile, I chatted with two wonderful ladies whose lives intersect with mine not often, but deeply.

By this point I had thoroughly lost my children. I went into the meeting space and looked around, confusedly, before a Friend pointed toward the children's wing. I went to check on them, and they were already in their "places of worship," engrossed in that work and at home in their place.

I returned to the adult meeting space and joined the song.

Tuesday, April 28, 2015

mini book reviews: the river why

I decided to start a series I'm calling "mini book reviews," because I read tons of books right now, and I don't have time to write full-fledged reviews, but I want to share them with you all anyway. I'm going to write whatever I can write in 15 minutes. Ready, go!

I'm starting with David James Duncan's The River Why, which I just "read" as an audiobook. Audiobooks are the best, by the way! I love listening to them while I'm cooking, doing dishes, gardening, folding laundry, etc. I get them from my public library.

This was my third time reading The River Why, and each time has been a very different experience. I read it in college for a class, and I hated it. I was so bored with the details about fly fishing and bait fishing that I didn't really see the humor or the philosophical poignancy of it. I think I pretty much skipped most of the last third and just read the end, so I missed the best parts. (Sorry, if you're reading this, Professor Higgins!)

The second time I read it, I loved it! My husband is a fly fisherman, so I had a bit of a vested interest in understanding the sport. Since I didn't have a time limit to finish reading it, I read it slowly and realized how funny it is. I was in a similar life stage to the main character, Gus, just growing up and leaving home, trying to figure out what life is all about, gathering folks who seem to know something about such things, and building a sense of who my people, my community, were going to be. I loved Gus's internal quests that required natural spaces as well as times sitting around reading books and/or talking to people. I loved the questions and the mystery, the hinted answers, the resolution, the humor threading through it all and the sense of the transcendent-immanent Ultimate.

Having been to seminary since reading the book last, this time I found myself analyzing Duncan's theology and philosophy with a more nuanced understanding. I agreed with some of his characters' philosophies, but there is also a subtle hierarchy, where he suggests through the philosopher in the story that the ultimate created being is humanity, the pinnacle toward which all other creatures want to climb. I struggle with this concept now, since it has caused so much harm to the rest of the created order.

Much of the philosophy I appreciated, however. I loved how he weaves together overtly Christian metaphors and stories with ideas of vision quests and finding God in the natural world. He doesn't force people to be Christian, but he leaves the door open. He expects them to find God in their own way, completely in their own bodies, when they're most in contact with the world around them.

I loved hearing Gus's story, but I also enjoyed overhearing (through his experience) the relationship between his parents. Reading it this time, I realized I see it from the perspective of the parents more than the coming-of-age young man. This made me feel old, but also just in the place I'm supposed to be right now, and I was encouraged by the joy and meaning that the two very different parents made with one another as they learned to truly be themselves without fear of the other.

I'm starting with David James Duncan's The River Why, which I just "read" as an audiobook. Audiobooks are the best, by the way! I love listening to them while I'm cooking, doing dishes, gardening, folding laundry, etc. I get them from my public library.

This was my third time reading The River Why, and each time has been a very different experience. I read it in college for a class, and I hated it. I was so bored with the details about fly fishing and bait fishing that I didn't really see the humor or the philosophical poignancy of it. I think I pretty much skipped most of the last third and just read the end, so I missed the best parts. (Sorry, if you're reading this, Professor Higgins!)

The second time I read it, I loved it! My husband is a fly fisherman, so I had a bit of a vested interest in understanding the sport. Since I didn't have a time limit to finish reading it, I read it slowly and realized how funny it is. I was in a similar life stage to the main character, Gus, just growing up and leaving home, trying to figure out what life is all about, gathering folks who seem to know something about such things, and building a sense of who my people, my community, were going to be. I loved Gus's internal quests that required natural spaces as well as times sitting around reading books and/or talking to people. I loved the questions and the mystery, the hinted answers, the resolution, the humor threading through it all and the sense of the transcendent-immanent Ultimate.

Having been to seminary since reading the book last, this time I found myself analyzing Duncan's theology and philosophy with a more nuanced understanding. I agreed with some of his characters' philosophies, but there is also a subtle hierarchy, where he suggests through the philosopher in the story that the ultimate created being is humanity, the pinnacle toward which all other creatures want to climb. I struggle with this concept now, since it has caused so much harm to the rest of the created order.

Much of the philosophy I appreciated, however. I loved how he weaves together overtly Christian metaphors and stories with ideas of vision quests and finding God in the natural world. He doesn't force people to be Christian, but he leaves the door open. He expects them to find God in their own way, completely in their own bodies, when they're most in contact with the world around them.

I loved hearing Gus's story, but I also enjoyed overhearing (through his experience) the relationship between his parents. Reading it this time, I realized I see it from the perspective of the parents more than the coming-of-age young man. This made me feel old, but also just in the place I'm supposed to be right now, and I was encouraged by the joy and meaning that the two very different parents made with one another as they learned to truly be themselves without fear of the other.

Thursday, April 23, 2015

writing elsewhere

Although I haven't managed to keep up well with this blog lately, I've been writing a lot elsewhere! If you'd like to read it, feel free to follow the links.

Of particular interest to those of you who follow this blog because of our Quaker connection, I had a couple pieces published in the last edition of Quaker Life Magazine. Kindred Courage connects my own life and ministry with the inspiring example of Elizabeth Fry, and the beautiful book of poetry about Fry by Friend Julie C. Robinson, Jail Fire.

Quaker Life also re-published pieces of the Peace Month 2011 curriculum, SPICE: the Quaker Testimonies, and SPICE: a Quaker Youth Curriculum.

I've also been writing regularly on the blog for the journal I edit, Whole Terrain. I've been enjoying talking with documentary makers and authors to review their work, and learning about all the excellent environmental thought and activism going on out there. As a "journal of reflective environmental practice," I feel like Whole Terrain's ethos lines up well with my own Quaker desire for the coupling of reflection and activism.

Here are some of my favorite pieces I've written lately:

Of particular interest to those of you who follow this blog because of our Quaker connection, I had a couple pieces published in the last edition of Quaker Life Magazine. Kindred Courage connects my own life and ministry with the inspiring example of Elizabeth Fry, and the beautiful book of poetry about Fry by Friend Julie C. Robinson, Jail Fire.

Quaker Life also re-published pieces of the Peace Month 2011 curriculum, SPICE: the Quaker Testimonies, and SPICE: a Quaker Youth Curriculum.

I've also been writing regularly on the blog for the journal I edit, Whole Terrain. I've been enjoying talking with documentary makers and authors to review their work, and learning about all the excellent environmental thought and activism going on out there. As a "journal of reflective environmental practice," I feel like Whole Terrain's ethos lines up well with my own Quaker desire for the coupling of reflection and activism.

Here are some of my favorite pieces I've written lately:

- DamNation: Whole Terrain interviews documentary filmmaker Travis Rummel

- Early Spring: Whole Terrain interviews Amy Seidl

- "Hottest Year": building trust in climate science

- Plastic Paradise: Whole Terrain interviews documentary filmmaker Angela Sun

- Nature's Trust: a conversation with author and law professor Mary Wood